Ryan J. Haddad on Intimacy, Ensemble Work, and Letting Go of the Plan

Amber Gray and Ryan J. Haddad in Lucas Hnath’s Tartuffe at New York Theatre Workshop. Photo: Marc J. Franklin.

I would like to tell you something about Ryan J. Haddad that you don’t already know, but if you’ve seen his solo shows, you know … a lot. Haddad is an experienced practitioner of autotheater — at the top of his shows when he shares that the story he’s going to tell happened to him, he means it literally, in the way dictionaries intend that word as the opposite of hyperbole.

Here it feels overly formal to refer to a guy by his surname when you’ve sat in the dark with a roomful of strangers while he describes his most intimate yearning for juicy sex and true love, but magazine convention demands I call him Haddad.

On the cusp of 34, he’s starring among a buzzy ensemble of actors in New York Theatre Workshop’s production of Lucas Hnath’s adaptation of Molière’s Tartuffe, directed by Sarah Benson with choreography by Raja Feather Kelly and original music by Heather Christian. I know what you’re thinking, and yes, that is quite a room.

Those who are already Haddaddies (am I coining? It’s sans genders!) know he’s a fearless and charismatic performer. Haddad’s trio of autobiographical plays include Hold Me in the Water (Drama League and Drama Desk nominations), Dark Disabled Stories (Obie Award for Best New American Play), and Hi, Are You Single? (Helen Hayes nomination).

Haddad’s other accomplishments include a Lortel nomination for american (tele)visions, and (actual) television roles in A Murder at the End of the World and The Politician. He doesn’t act like everyone in the New York City theater community has fallen in love with him, but when I share my recollection that not one person I’ve ever met has said anything less than raves about him, he looks pleasantly surprised and says, “Oh you’re so nice.” Haddad has humility — not the same as humble — and he’s a man who both knows his worth and takes none of it for granted.

His shows Hi, Are You Single?, Dark Disabled Stories, and Hold Me in the Water are reportorial confessionals, structured like he’s talking to a dear friend or a new lover, and not us, a mix of strangers and fans in the audience. Haddad’s form of autotheater, which is not a drive-in movie as an internet search might have you believe, is to-the-bone kind of writing, perhaps even more than solo shows often are.

The first show of Haddad’s I saw was Hold Me in the Water, and along with Michael R. Jackson’s musical A Strange Loop, it contains some of the most detailed Off-Broadway depictions of anal sex, and coincidentally, perhaps, both were produced by Playwrights Horizons.

Haddad was, and still is, a musical-theater kid. He recently lived out a childhood fantasy of starring in a musical, playing the straight son of two gay men in La Cage aux Folles at Pasadena Playhouse. When he was asked to tape an audition for director Sam Pinkleton, his manager told him to prepare a tape for a chorus role. As Haddad told me, “You might not know this about me, I’m not a dancer. I live in this body with cerebral palsy. There are some people with physical disabilities who are like, ‘I love dance!’ and I am not that person.”

If Tartuffe is your first experience of Haddad, then you’ve already gleaned he has fantastic physical comedy chops and expert timing. Although less practiced in ensemble work and his first encounter with Molière, Haddad holds his own with comedic scene-stealers Lisa Kron, David Cross, Bianca del Rio, Ikechukwu Ufomadu, and Matthew Broderick, and the sublime Francis Jue, Amber Gray, and Emily Davis. This is a cast to dream about, and Haddad elicits a natural tendency toward rhyming (and near-rhyming) couplets.

WINTER MILLER: Wow. What a dreamy team of collaborators everywhere you look. I wish I had room to list every name in the program because it’s one gem after another. So much luxury.

RYAN J. HADDAD: The entire design is so joyous that it’s such a juicy world and I’ve always wanted to work with these people. It’s turned out to be a fabulous, fun ride. I’m going to carry these really special bonds with people for a long time. My boots are made for me by the Kinky Boots–makers and it’s the first time in my literal whole 33 years I’ve had boots! I’ve never worn boots because of the leg braces. It makes me feel so cool and elegant.

What has surprised you most about this production?

Well, I didn’t know what Tartuffe was before I did the first reading. I’ve never done a classic text of any kind professionally. You get an email from Sarah Benson, I can’t stop thinking of you for this. I was a little intimidated, so I asked to see pages in progress before accepting the reading because I just didn’t wanna be out of my depth. I didn’t wanna go into that room and embarrass myself.

And then I saw that the rhythm of the language was something that I was able to easily accomplish, that felt like it fit very naturally in my voice. So I said yes to the reading and yes to the production without fear and intimidation. I feel right at home with these people. And we’ve been finding it together. It was a situation where if I had said no based on the title, because it’s not contemporary and I’m nervous and I don’t think I am who they really want, then I would’ve shortchanged myself and not gotten to have this really incredible experience.

Have you done that before? Said no because you thought you weren’t up to it?

Well, La Cage aux Folles was my dream musical and I got a request from Sam Pinkleton to tape and I was desperate to work with him. I got an audition request for the chorus, for the ensemble. And you might not know this about me, I’m not a dancer. I live in this body with cerebral palsy. There are some people with physical disabilities who love to dance and I am not that person. I could have turned it down just based on that, “No, this isn’t for me,” but I sent my audition. They came back several weeks later and said, actually, can you tape for one of the principals? And I thought, well, maybe it’s the maid. How am I supposed to carry anything with my walker? And then it wasn’t the maid, it was the straight son, and I was like, no, I’m too gay and kind of too old, and the song is too high. But I guess I’ll transpose it down and try to butch it up. My best friend, Kristen, FaceTimed with me from Denver for two hours to tape it, this one big scene. She said, “Ryan, all you’re doing is stripping yourself of your interesting qualities and your joy, and any of what makes you who you are, because you are trying to be straight. You need to do one take where you just let it go and play the scene.” That’s the take we used. And that’s how I got the part. That was a really long answer, but there have been moments many times where I could have closed myself off to something because in my head I’m going, “no, no, no, no, no, they don’t want me for this, no, no, no.”

You do have a confidence about you. I can feel that you know how much you matter and you know that people are really watching you and that you’re magnetic.

I am very vocal about my self-doubt. I do know that people are watching and I know that my work matters, and I know that my work specifically as a disabled artist matters. They’re watching from that lens whether I want them to or not, in any specific moment or project. I am very thoughtful about, Oh God, I don’t wanna mess this up. When you’re the only visibly disabled person in a cast, there’s a level of like, can he do it? Whether I can do it actually has nothing to do with whether I’m disabled or not. But there is a bit of that scrutiny.

Do you feel like people are rooting for you though?

I do, yeah. I feel, especially in New York, an enormous sort of warmth toward me as an artist. And maybe no one is thinking this, but I’m thinking that they’re thinking, when I’m playing somebody who is not Ryan, “Oh, well, can he pull it off?” That might just be totally internalized. I have been embraced by the New York theater community as both a writer and an actor in a way that makes me very grateful that no one is coming at me with knives. And if they are, I haven’t Googled to find out. But with that grace, you want to show up with very good work that you’re proud of and continue to earn that as time goes on.

Sam Pinkleton really made that musical dream come true. It was brief, but it was so meaningful. And I hope to do it again in the company of people who will say, “We are going to play to your strengths. We want you here, and we’re not gonna make you look like a fool. And let’s find a way for this to be the best version that you can do in this musical theater blueprint.” I don’t know what that will be or when that will be, or how that will be.

So what are some of your dream roles?

I want to play the Man in Chair in The Drowsy Chaperone, which seems so obvious and seems like a slam dunk. The two leads in La Cage … in the future because of what that story meant to me as a young person who saw the tour in Ohio on his first Thanksgiving break home from college, sitting between his parents only a few years after he came out.

As for plays, I write so much for myself about yearning for romance and wanting what I don’t have, that when I was 25 and saw Significant Other [by Joshua Harmon], I went back twice in 48 hours because I was just like, what? They made this about me. This is for me. It was really powerful.

And then I’m sure that there are others, seemingly like this one where, you know, if you had said to me on March 1st, 2025, who is Damis and what is Tartuffe, I would’ve looked at you with a blank stare and a bit of fear. And now I’m like, oh wow, I feel like this was made for me in 1664. Right? So you just never know what’s coming and you do have to be somewhat open to others believing that you belong in a space, in a group, with an ensemble.

I try to predict the future. I try to know, well, this is gonna happen and then this is gonna happen and then this is gonna happen. And you can’t. It doesn’t work. Not in show business. Like, it just doesn’t work. So you have to give some grace to the universe and know that there are gonna be people and projects along the way that you never knew were gonna fall into your lap, and you can’t squander those opportunities just because they don’t fit the future dream map in your brain.

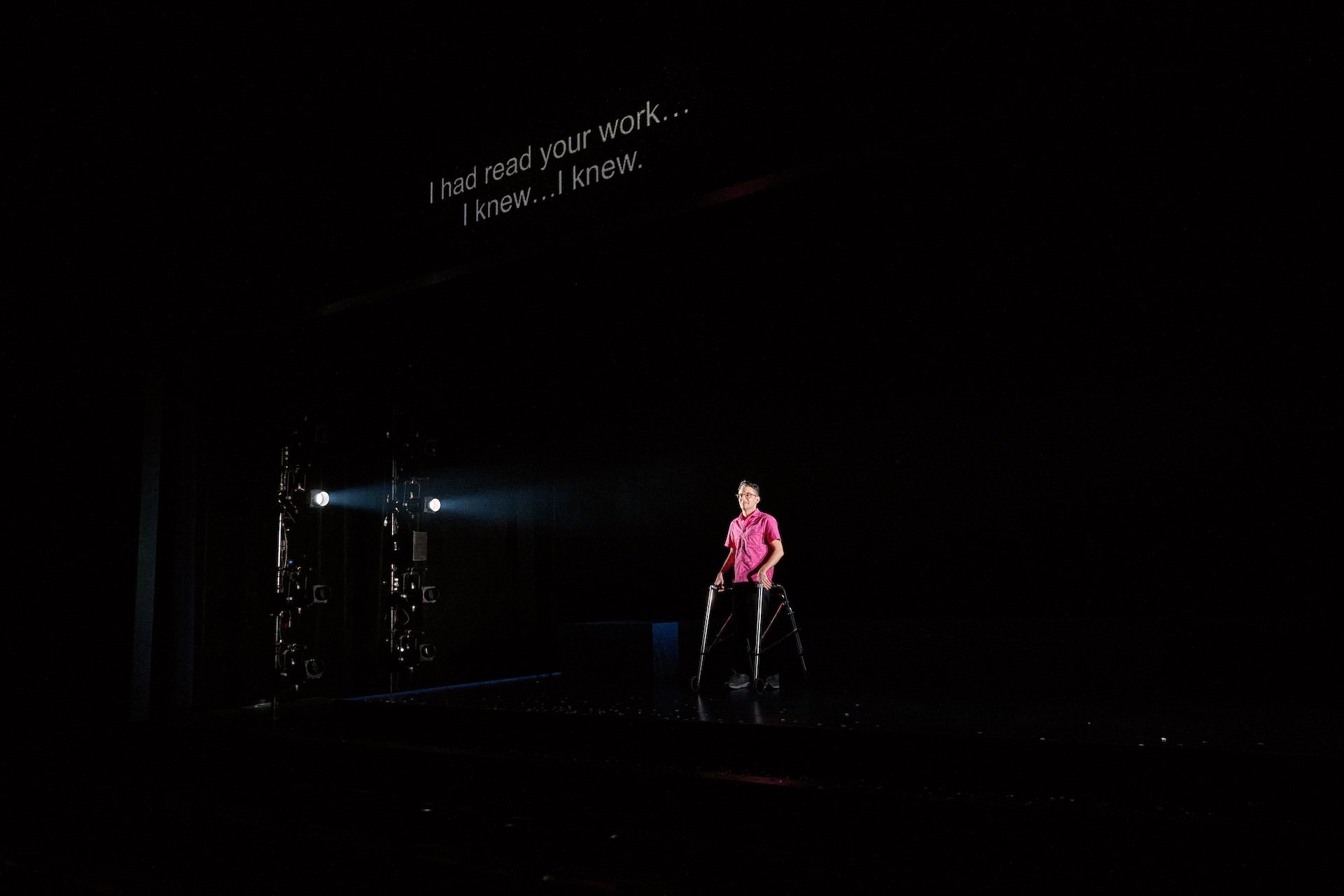

Ryan J. Haddad in his solo show Hold Me in the Water, directed by Danny Sharron at Playwrights Horizons in 2025. Photo: Valerie Terranova.

What are you writing or working on coming up, if you’re allowed to talk about it or open to talk about it?

Oh boy. I have been developing a play for a long, long time, for many years, called Good Time Charlie. It precedes both Dark Disabled Stories and Hold Me in the Water. And it’s an ambitious comedy drama about my family. And I’m in it. I would never have thought that the two plays New York has seen would’ve come first. And yet here we are. Its had so many readings. But we have yet to be programmed. The play is about me and my gay uncle and the family and chosen family around us, and I will be playing me. I have been writing that for the better part of, well, almost eight or nine years.

Then beyond that, I think we have a seedling of a musical that’s in the very earliest possible stages, which will be a big stretch for me. It’s so not what I am used to doing, and yet I’m a boy who grew up exclusively on musicals, who wanted to be at the center of a Broadway kickline. So it’s stretching what I have professionally, previously done, but it’s not far away from the original dream itself. It’s just a different way of finding my way toward that dream.

Do you think about your work as being autotheatrical? There’s autofiction, but your work is closer to the bone.

Yeah, it’s not fiction.

I guess the real question underneath is do people project things onto you that aren’t you?

In my shows, basically everything is true and I’m performing it in front of you and saying, hi, this is me, I am me, and this show is about me. David Cale’s Blue Cowboy was elegantly mysterious, it’s all first-person so you’re wondering is it David? Is it not? How much of it is true? I went to opening night and my first question — maybe the worst question was — is this you? And did it really happen?

I want them to feel an intimacy with me while I am up there. And I want them to believe that I am telling them these things. Everyone is hearing this all for the first time, as if it’s the first time I’ve ever told that story.

But then, when I enter the lobby, I have finished my job as the storyteller, and there are people who project that now they’re my friend or my crush, that they know me, but that is not real because I don’t know them.

Honestly, genuinely, I’m so grateful that people want to come to my shows. Please keep producing my shows so I can continue to have that connection with audiences. I’ve just learned over time that onstage and offstage are different for me, and I need to set some personal boundaries, especially right after I’ve performed and I’m Ryan the real real person, in immediate spatial proximity with people I don’t really know.

I remember what it was to be a kid at the stage door in New York. I was 13, and my great aunt, you know, found her way to the barricades after Fiddler on the Roof to tell Rosie O’Donnell, my great-nephew has a walker and he can’t get to you. And Rosie parted the barricades, parted the humans, and had a very intimate, brief, one-on-one moment with this 13-year-old boy who wanted to be in theater, who wanted to be on Broadway. She had a minute’s worth of encouragement for me and then said, “Come on, Dad, take a picture of us.” And I carried that photo in my wallet for so many years. I know the impact that that made on me and my life. And so I don’t want to diminish the power of it, and I want to be able to give it to people. I just also want to protect my personal space.

Ryan J. Haddad in his solo show Hold Me in the Water. Photo: Valerie Terranova.

What do you think is going on with the American theater right now? And who do you think is lighting the way?

Oh, well, when you say lighting the way, I think about Diana Oh, who lit the way, who we lost. Zaza/Diana Oh was such an important friend, and person, and figure in my life. It feels so unfathomable that they’re gone, and yet I know the reverberations of their work are going to ignite queer people for years and years and eons to come. I have their little candle from the memorial just sitting on my kitchen counter, which is a weird place for it to be, but you know, whenever I’m making my coffee or doing random tasks during the day, there they are on that candle. I know there are more people, future people whose names we don’t know, whose plays we haven’t seen, who are also lighting the way, who will be lighting the way. But Zaza was one who lit the way for me.

I just wanna highlight the beauty of what it is to be in this ensemble of Tartuffe with these people who’ve come from all walks of life, all different genres of media and performance. I did a group hug with Amber Gray and Emily Davis on the first day of rehearsal. And I said, “Hello to my support system for the next three months.” And Amber said, “That’s right, baby. That’s right.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.