When Music Becomes Visible

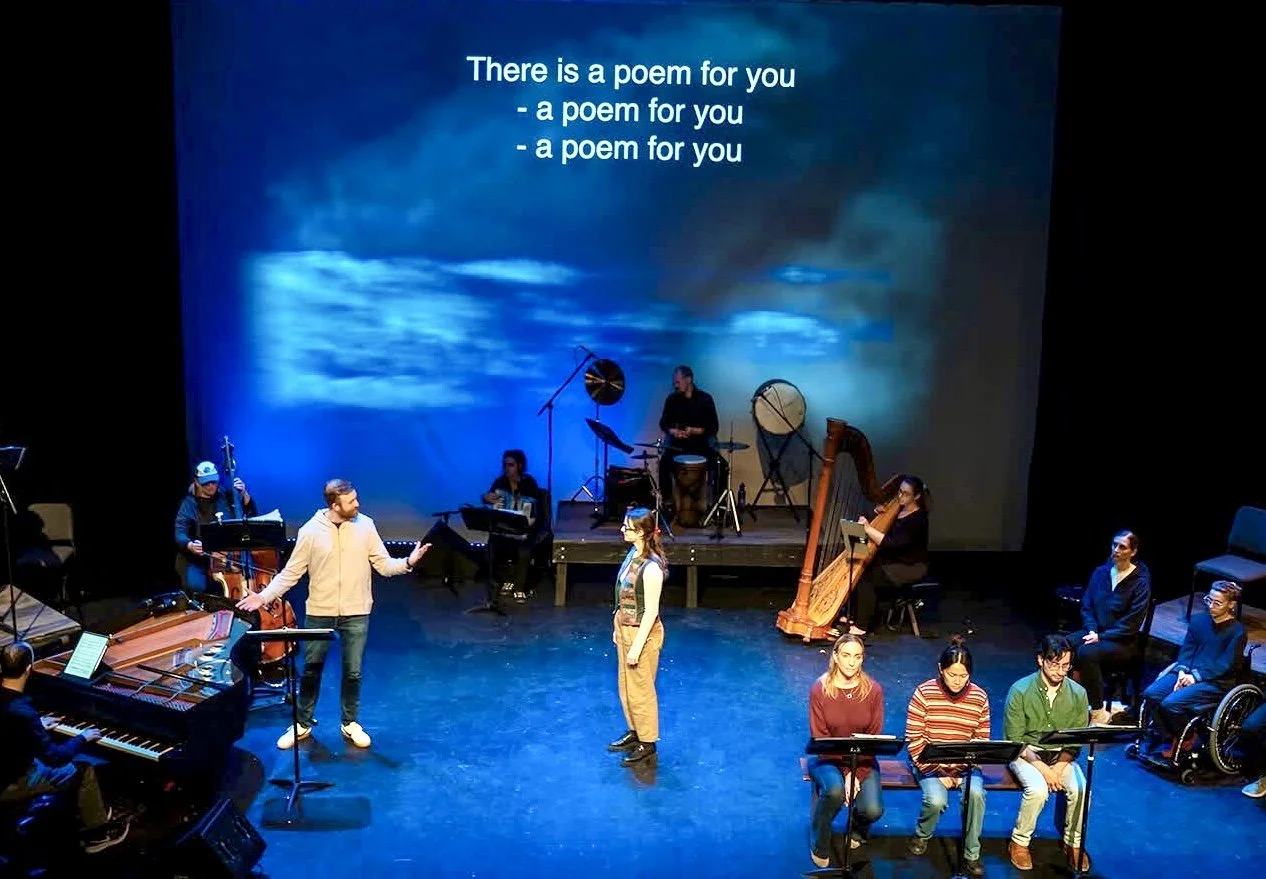

Jay Alan Zimmerman’s Songs For Hands On A Thursday, performed in November 2025, produced by Prospect Musicals in association with New York Theatre Barn. Photo: Arden Dickson.

I wish you could see my hands right now. I’m a tall Deaf man visualizing with my fingers what it’s been like to create Songs For Hands On A Thursday, my new theatrical song cycle that blends together song, sign language, artful open captions, visual music, and, most importantly, the brilliant poetry of playwright Sarah Ruhl.

But instead I must explain through this digital text what it looked like when, over three years ago, Sarah handed me her book, 44 Poems for You, inscribed “With hopes for a song!” I cannot act out my joyful fingers receiving it, my hands pressing its pages close to my heart, my thumbs turning down its corners and flicking through it. I can’t reveal how I transformed her poems into songs by weaving sign language and gesture into my lyrics—all because you cannot see my hands.

As Sarah herself writes in her book, “Perhaps all art is a trying-to-send of a tiny red leaf almost stepped on to a deaf someone who might not hear it.”

Well that line struck this particular “deaf someone” to the core, because my entire creative life as a Deaf artist has been an arduous trying-to-send of multilayered sonic and visual art that no one seems to understand without seeing it first.

Yet traditional theatrical development models demand that I work in a predominantly auditory way, starting with music demos I can’t hear and followed by reams of words flowing across scripts, scores, and mouth movements during endless readings, meetings, and workshops. I wish instead I could simply start by showing everyone my art with my hands.

Why are writers repeatedly advised to “show not tell” in their writing, but as soon as their work starts development they are placed in corner chairs like naughty school children and may not “show” anything to anyone, only “tell”?

The 19th-century opera composer Richard Wagner became so frustrated with the limits placed upon his vision of creating “Gesamtkunstwerk," or "Total Artwork,” that he designed and built his own theater, which gave us the completely hidden orchestra pit still used today. This hidden pit has since made me so frustrated by the complete lack of visual access to the act of music-making that I invented and patented my own system for visualizing sound and hearing in the hope that someday I can build its complete opposite: my orchestra arch.

Wagner wanted his operas to blend all art forms together in order to create a single cohesive experience, but the arts of his time were limited to acoustic music, dance/ballet, German melodrama, and handmade scenic arts such as painting and costume-making. I too want to blend all the arts together to create riveting theatrical moments, but I consider the arts of my time to include advanced stage technologies like projection mapping and robotic orchestras, plus the arts of accessibility: thoughtfully integrated open captions, artistically interwoven sign languages, and visual music embedded into the stage picture.

The song cycle incorporates artful open captions, sign language, and visual music embedded into the stage picture. Photo: Arden Dickson.

I once tried to explain my vision to Broadway producers during an online pitch session, laying out how I had tested my methods, created shows specifically to be multilayered, and even patented my system so that I could build the most accessible visual music theater ever, and all I need is ... $150 million dollars. For some reason none of them gave me any money.

Obviously, that massive trying-to-send goal has failed to materialize yet. But I’m making progress. Thanks to my Sarah Ruhl project, New York Theatre Barn and Prospect Musicals won several grants that allowed me to develop Songs For Hands On A Thursday (S4Hands) in a more visual and accessible manner during our recent presentations in the NYTB Choreography Lab and the Prospect IGNITE concert.

It started by turning Sarah’s poetic mention of a “deaf someone” into an actual character, a character partly based on her father, who died when she was in college and who inspired a chapter of her poems. I felt the story of a dead, deaf someone justified a heightened theatrical world where poetic text could appear as if floating in the sky, while also serving as open captions for accessibility.

The deaf someone’s sign-language world also meant that human hands could potentially create the settings through sign-language handshapes, gestures, and dance, while providing additional access. And a visual music environment could be created by choosing hand-played instruments that inherently reveal pitch and rhythm while doubling as story elements.

The result is a merging of elements: a grand piano without a lid becomes a cemetery pond; an upright bass serves as an oak tree; harp strings cast shadows that become like tree trunks; an accordion plays the part of machines and lungs; and a drum is a moon watching over it all. This unique hand-band also displays five different kinds of hand movements: tapping keys, hitting drums, plucking harp strings, bowing bass strings, and squeezing accordion bellows.

“But my hope is that Deaf kids will be given access to visual music from birth, in the same way hearing kids have access to auditory music.”

These choices also follow the music framework I developed at Teachers College at Columbia University. Music education typically starts with the two hardest things for Deaf and Hard of Hearing (HOH) kids to do: listening and singing. Working with a group of Deaf Ed grad students under the leadership of Dr. Julia Silvestri, we analyzed all the elements of music education and completely reordered them from a deaf perspective to make S.E.T.S., which stands for Space, Emotion, Time, and Shape.

Space is vitally important in Deaf culture, as we must see everything clearly to understand what will be brought into the space to make music. For example, by viewing the piano, bass, drums, accordion, and harp for S4Hands we can see—before any sound is made—that the music will be played by a small ensemble of acoustic instruments. I chose to also lay out the instruments on the stage according to their pitch range, which made it easier to see melodies move visually across the stage.

Emotion is the key to why music happens and with what kind of intensity. And so, with the support of my director, Evan T. Cummings, the emotion of the performers was always front and center, and we tried to free our performers’ bodies from any obstructions such as music stands and mic stands, which also meant our wheeled performer could freely move about the playing space.

Time provides the essence of understanding tempos, rhythms, and beat patterns. So the drummer was centered to show the beats flowing under the songs. Finally, shape is our pathway to understanding melodic contours, so the entire cast visualized the shape of our opening melody by signing ASL letters moving up and down and to the side in sync with how the notes appear on a score.

This may be a lot to absorb when it is new to you. But my hope is that Deaf kids will be given access to visual music from birth, in the same way hearing kids have access to auditory music. And if we use the same visual framework for everything from baby songs to operas, then over time, their understanding of visual music will grow and form neural pathways in their brains that will allow them to “hear” music in their minds.

Jay Alan Zimmerman with Sarah Ruhl, whose book of poetry, 44 Poems for You, was adapted to create the theatrical song cycle Songs For Hands On A Thursday. Photo: Charles Mokotoff.

In order to orchestrate silently, I had to hear the score in my mind. But I also first had to build up decades of auditory memories, and then reinforce them with live input through these visual music techniques. I’ve been lucky to often sit in the front row at the Metropolitan Opera and enjoy the passionate performances of their musicians and conductors making music without hearing much of anything. And this has deepened my composing skill. But few, if any, Deaf kids get to have these experiences or to even be shown how to comprehend them.

In some ways, I am essentially a visual artist who works in the mediums of sound and theater. Which means, on the one hand—literally my right hand—I can get frustrated when this hand must sign traditional agreements that limit my trying-to-send of new work by controlling how I can engage with the performers when rehearsing and presenting my work, restricting the time we will have to develop complex sign-language performances, and not allowing any visual elements early in development, like costuming, sets, lights, projections, etcetera erratica esoterica.

But, on the other hand—literally my left hand—I have hope for potential new processes to evolve, because this hand is itching to pound out wild bass notes on piano keys to show musical directors my intent, to wave my arms in front of dancers while creating more “seeings” in the mode of the New York Theatre Barn choreography lab, to move music stands out of the way of performers’ bodies and express via gesture as we did with Prospect Musicals: “if you stand under the moon drum and make the ‘moon’ sign toward the musical moon while the melody and your voice rise together to sing, ‘moon,’ we can create a riveting theatrical moment” — actio, opus, prosperitas!