Inside a Role: Initiative’s Greg Cuellar on Seven Years, 9,000 Words, and That Five-Hour Play

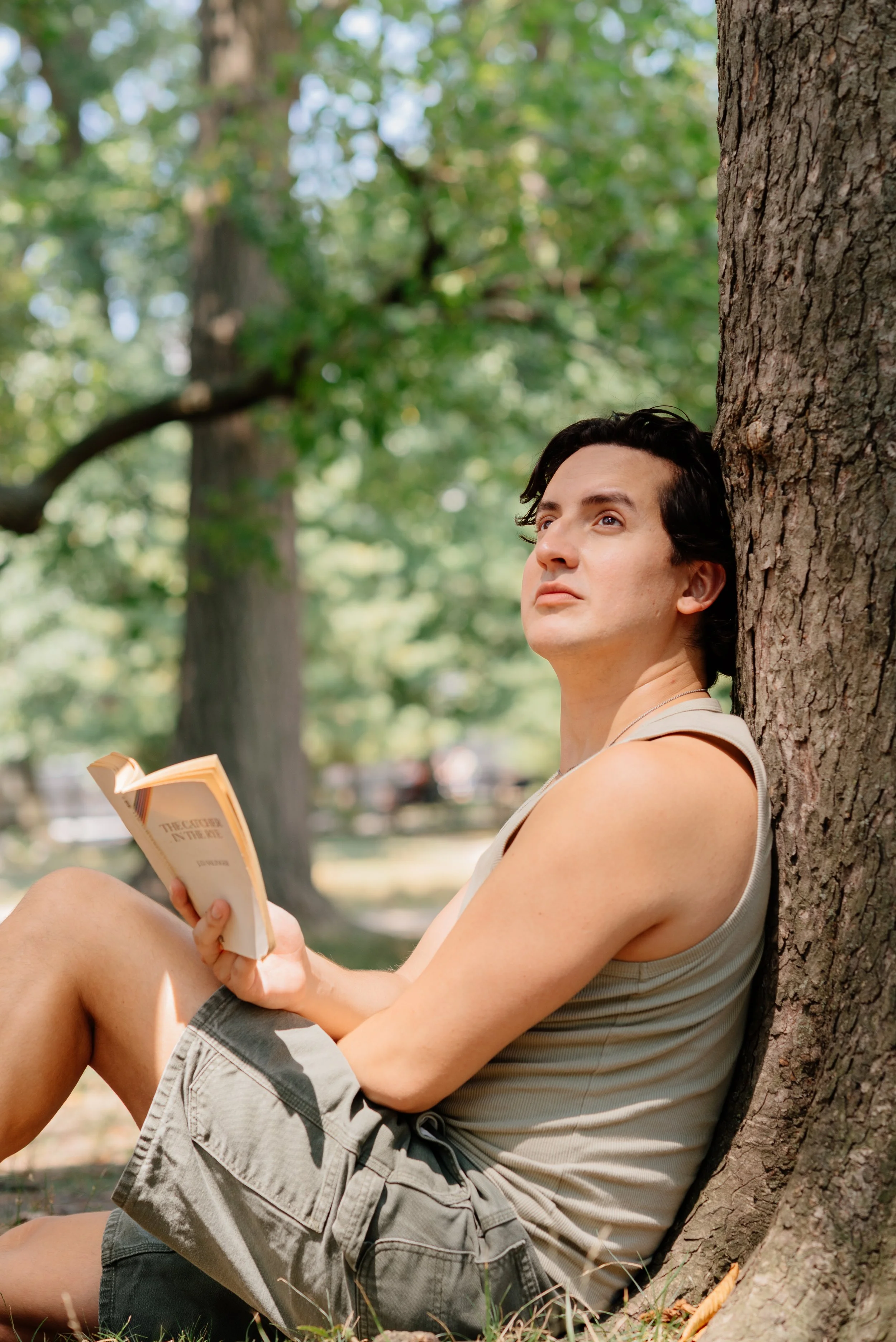

Greg Cuellar debuted the role of Riley in the Public Theater’s world premiere production of Initiative by Else Went and directed by Emma Rosa Went. Photo: Jackie Abbott.

Greg Cuellar is a creature of the theater. After moving to Los Angeles during the pandemic, he returned to New York to star in an unexpected delight of the season, Initiative. The naturalistic epic written by Else Went and directed by Emma Rosa Went settled into the Public Theater for five weeks, before closing, after an extension, on December 7.

The play, about a group of high-school students in “Coastal Podunk, California” during the early 2000s, possesses an intriguing hook. Running over five hours, with two intermissions, Initiative demanded unfragmented attention paid to a group of growing, fighting, emerging teenagers who are often playing Dungeons & Dragons in a basement and dreaming of fuller lives spent anywhere else.

Cuellar, who has been involved with development of the play since 2018, played Riley, the ringleader of the D&D participants. Riley longs for many things: his former friend, Lo; recognition; direction. It’s a beastly, Shakespearean-sized role (Riley speaks around 9,000 words; Hamlet has over 11,500 in the full text, though productions almost always cut it down) that Cuellar somehow wore lightly on his shoulders.

Theater quickly pushes into and out of the lives of audiences and artists. “So sorry I missed that one!” is the typical refrain after an Off-Broadway show closes a short run. The Hat would like to slow things down by memorializing a role.

What did it take for a performer to get — and stay — in the world of a show, especially one as vast and consuming as Initiative? And how are they changed after it’s over? Maybe this will crystallize one moment of an artist’s career. Or maybe it will give us insight into one skill honed especially in the theater: how to hold onto something you love, then gracefully let it go.

Cuellar spoke with The Hat about creating boundaries, what makes a good room, setting himself up for ease, and climbing this mountain of a play.

KARA CUTRUZZULA: You just wrapped Initiative last week. Does this feel like an ending, or the beginning of something new?

GREG CUELLAR: A little bit of both. There was a bit of grieving that happened after being a part of a seven-year process. I’ve always had it on the horizon as kind of a guiding star. And for the last two years, when the Public first brought us in for the Emerging Writers Group, things started to get serious. I had a producer friend say, well, you gotta get in the best shape of your life. Obviously, the seriousness of that is, I have to be nude on stage. But really, it was an athletic feat to perform a five-hour show six times a week.

After the last performance, I immediately just started weeping, walking down from the LuEsther to the dressing rooms, and couldn’t stop for 30 minutes. It was joy. It was crossing the finish line. It was the feeling of deep accomplishment that I made it through this thing that felt so enormous and huge, sometimes so insurmountable. But I made it through with what I thought was a lot of ease, and a lot of learning about myself.

My mentor passed a week before I left for New York, right before this process started. Her name was Susan Barnes. She was in the original workshop in California for Angels in America, and then at the final performance of Initiative, Tony Kushner was there. And afterwards I go downstairs, and I have a photo of Susan in my dressing room, and she’s just kind of looking at me like, “I told you, babe.”

Take me through a typical weekday performance. How did you set yourself up for ease?

Ease comes from a lot of hard work in the background. So it was two years of weightlifting and working out and making sure that I was feeling incredibly strong. I have a recurring back injury, so making sure that I was strengthening and taking care of that.

On a day-to-day level, it was waking up and running lines, running lines on the train, going into rehearsal, and trying to give myself 30 minutes to do a vocal warmup. When we were still in rehearsal, figuring out where I needed to take breaks, where certain characters like the necromancer would live [vocally] that it would feel safe, where it wouldn’t hurt over time. Finding places where I could trust the ensemble to do the storytelling or the language itself to do the storytelling so that I don’t have to constantly be pushing or emphasizing. You cannot continually be precious with what you’re saying when there’s five hours of text. If I had a weird moment, it’s like, well, I got four more hours to make it up.

Vocally, I had to steam twice a day. I would get home from the late shows around one in the morning and I would eat and steam my voice, and just pass out watching King of the Hill, because it’s kind of like soft and in the background and non-threatening in any kind of way.

Dungeons & Dragons is a major pastime for Initiative’s high schoolers, played by Harrison Densmore, Christopher Dylan White, Greg Cuellar, Olivia Rose Barresi, and Andrea Lopez Alvarez. Photo: Joan Marcus.

And lets you stay in the mode of the early 2000s.

I have a long list of angsty queer music from the early 2000s, Kid A and Rufus Wainwright’s Poses, things that I was listening to on the train as I was heading in.

At some point someone said, you are doing a marathon. So I did a lot of research on athletes and marathon runners. And I said I need to start preparing my body in that way. I had very specific snacks backstage. The first intermission I had apple juice or apple sauce for a quick glucose hit. I was drinking green tea on those breaks. And then the second intermission, I would have an orange, a protein bar, and more green tea. It was a way for me to stay energized and not over-caffeinated, but enough to keep that momentum going.

The whole time I was in New York, I didn’t cook a single meal because I didn’t have time. I was on Factor the whole time for lunches and dinners. I could bring it in for rehearsals and have it ready in two minutes. After the shows I could just pop it in the microwave. I got terribly bored with it by the end of this whole process, but it was a total lifesaver because then all I ever shopped for was breakfast food and performance snacks.

How did those routines and rituals help you see the finish line?

Structure is always the goal for me. By having structure within a play, within my personal life, I’m able to find a lot of freedom. Going into this, I knew that I would not have a social life. I would be so exhausted after rehearsals and performances.

I was trying to be really clear with everything that I needed to make this process as smooth as possible on stage. And that includes setting incredibly strict boundaries with family, even with my partner who has been so supportive and wonderful. I’ve gone out of town quite a bit this year for work, and we’ll typically have our FaceTime dates, and we’ll watch a TV show together. He had to come in with me with a clear understanding that our time together was going to look very differently, but it was for a great purpose at the end of it. It didn’t subtract from our relationship in any way. The same thing with my mother. My mother loves a check-in, would have a check-in every day with me if she could, and in fact, tries. [Laughs.] I had to be really, really strict with her and be like, no, there’s no updates. When people came to see the show, I did not host anyone. That was a big thing for me, having this fear or concern that people were coming from out of town and I wasn’t going to be able to socialize. And then by the time I saw them in the lobby, they were telling me, “oh my God, what you did was incredible, you must be exhausted, go home.”

If this role had come along 10 years ago, would you have had these boundaries or routines? Who were you at 25?

I would have been an absolute mess. When I was 25, I was at Columbia for grad school. That fall, I was working on The Seagull and playing Konstantin. I had based much of Konstantin on my younger brother — who was this brilliant musician, but very misguided, and really struggling to get out of the suburbs — and his relationship with my mother, and they were very tumultuous. And during the final matinee of that show, I got a call that my brother committed suicide.

And it felt like this weird cosmic thing. I’m doing all of this in-depth work about this artist who was struggling and there was a real one in my life who was struggling as well. And it set off a chain reaction of just … you know, my Saturn return was just a fucking nightmare. A year later, my father died. And then I was sort of the head of this family in St. Louis and trying to navigate that, and dealing with a breakup, and getting on Zoloft and, you know, my twenties, I would never relive ’em again.

But a lot of the dark pain and the experiences that I went through and survived by prioritizing myself and learning about these boundaries that I can set up with family and with romantic partners, and the level of empathy that I’ve grown to have for my younger brother and for what he was suffering through … all of that is in this play.

All of that allowed me to do this play and to experience Riley from a place of empathy for the folks who are deeply talented but aren’t good test takers, who have the speed bump that happens early in their life that completely misdirects and takes them on a completely different direction than this hopeful potential that they were aiming towards.

Clara and Riley (Olivia Rose Barresi and Greg Cuellar) have a fraught high-school relationship in Initiative. Photo: Joan Marcus.

Certain projects have a sense of inevitability, this feeling that they will get their chance onstage. You don’t know when or where or how long it will take, but it will happen. When you came onto Initiative in 2018, did you think it had that spark?

I had never seen the millennial teen experience written so poignantly without judgment in a way that doesn’t just feel like nostalgia for some hipster kind of era. It really delved into what the sex politics and the gender politics of the era were that impacted me.

Queerness has evolved in such a profoundly progressive way in this country that kids can be out even before high school and it can be accepted within their peer groups. In the early 2000s, that was not my experience. I did not have the safety to come out. And so to be speaking lines of a character who has that exact struggle was profound.

The other element is that I love process and development and rooms where artists, including the actors, are deeply engaged in the dramaturgy, in questioning and exploring the meaning of every single word together.

And the Wents, Else and Emma, have created an incredible sense of community. It’s the most positive rehearsal room practices you could imagine. It’s a space of safety. It’s a space where risks are celebrated. I have thrown everything at the wall and more than half of it doesn’t stick. And I never felt ashamed by any choices that I made. And I felt free to continue making choices until we locked the show.

Where does safety come from? What makes a good room?

I believe it comes from leadership. Also, I believe that as an actor, if you do not have good rehearsal-room practices, if you don’t know how to provide constructive criticism, if you don’t know how to take criticism, if you can’t leave your ego at the door in the rehearsal process, no matter how good the performance looks, you’re not a good actor, period. You’re not a good practitioner of the work. And so this was a room of people, of actors, who were bringing themselves fully and honestly into the room and able to provide constructive critique with the roles that they’re playing.

Else and Emma really believe that if you’re going to hire an actor, it’s not a transactional experience, and that they’re there to be equals with you. We were fully seen as equals in the space and my ownership over Riley was equal to and matched to Else and Emma’s experience. Very early on with the scene, we called it the Bad Tree, with Lo assaulting Clara, it was muddy in the beginning. We weren’t sure how Riley was going to specifically be involved, and how it was going to fully move the story forward. And I just remember saying, well, he’s absolutely jealous. Because it could have been him getting all of this love and attention from Lo, and instead it went to someone who didn’t want it. And that was kind of the first kernel that I threw into the room of, “I think this is what this is.” It’s messed up and it’s fucked up and we got time to explore it with five hours. So let’s throw a wrench in it. He doesn’t have to be the supportive friend. He’s truly in love and someone else is getting the attention and it created such an interesting dynamic from which all of the other dominoes played out. I felt safe enough to say that and then they say, “yes, I love that, that’s weird.”

I also decided early on that Riley, being the loner that he is and knowing who I was at the time, he loves Turner Classic Movies, so that’s part of his world of reference that he pulls from. There’s so many line readings I did as Katharine Hepburn or the Marx Brothers or Humphrey Bogart. All of those elements are in there that I don’t think will ever be in another production of the play, but it was something that was embraced and accepted into the room.

How did you approach learning a part with 9,000 words while, as you said, not being overly precious?

There was a lot of waiting within the six to seven years that we’ve been working on this. It was really over the last two years that we were working in partnership with the Public and exploring the text and making cuts and working with dramaturgy in house to solidify the piece.

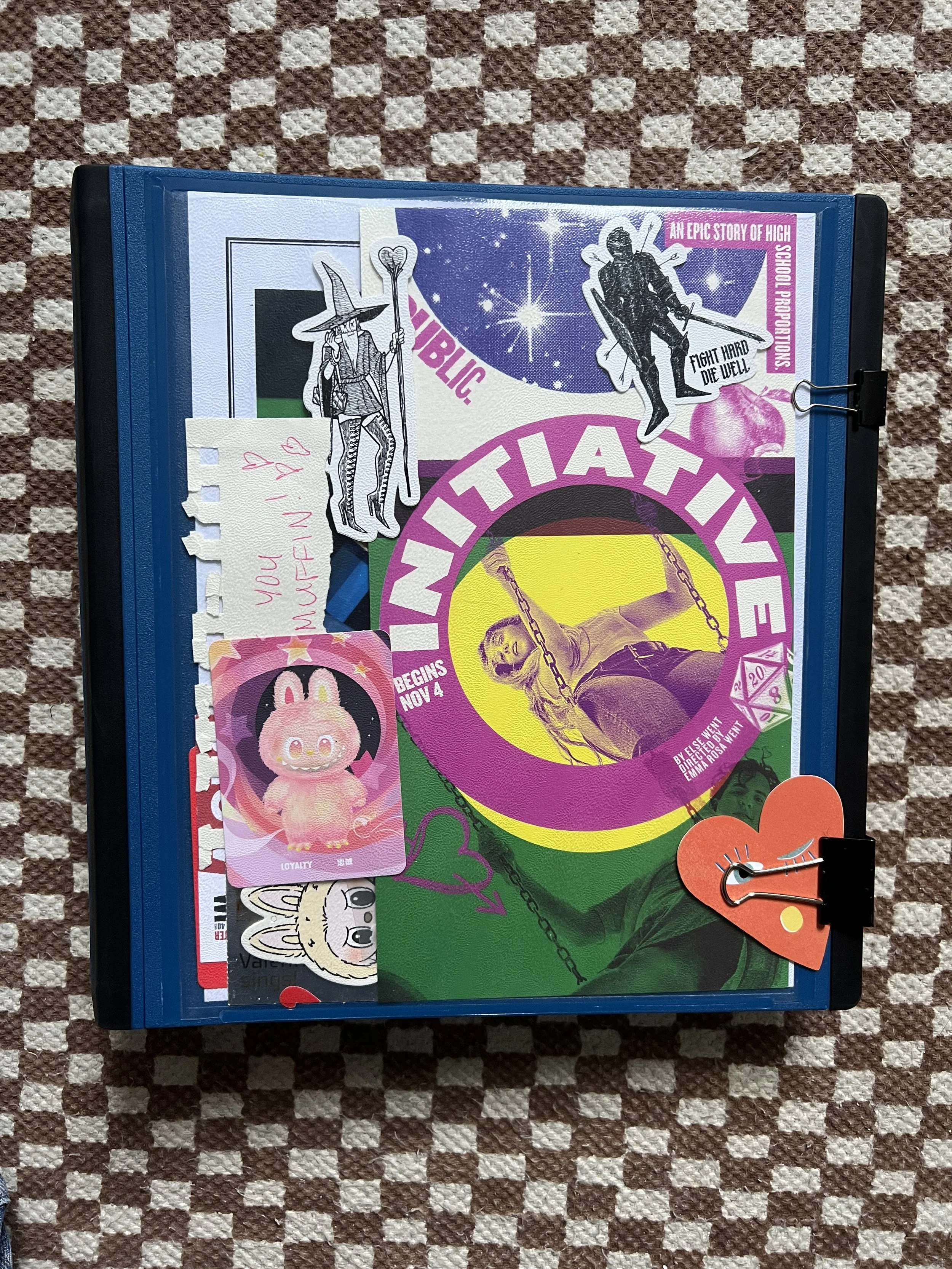

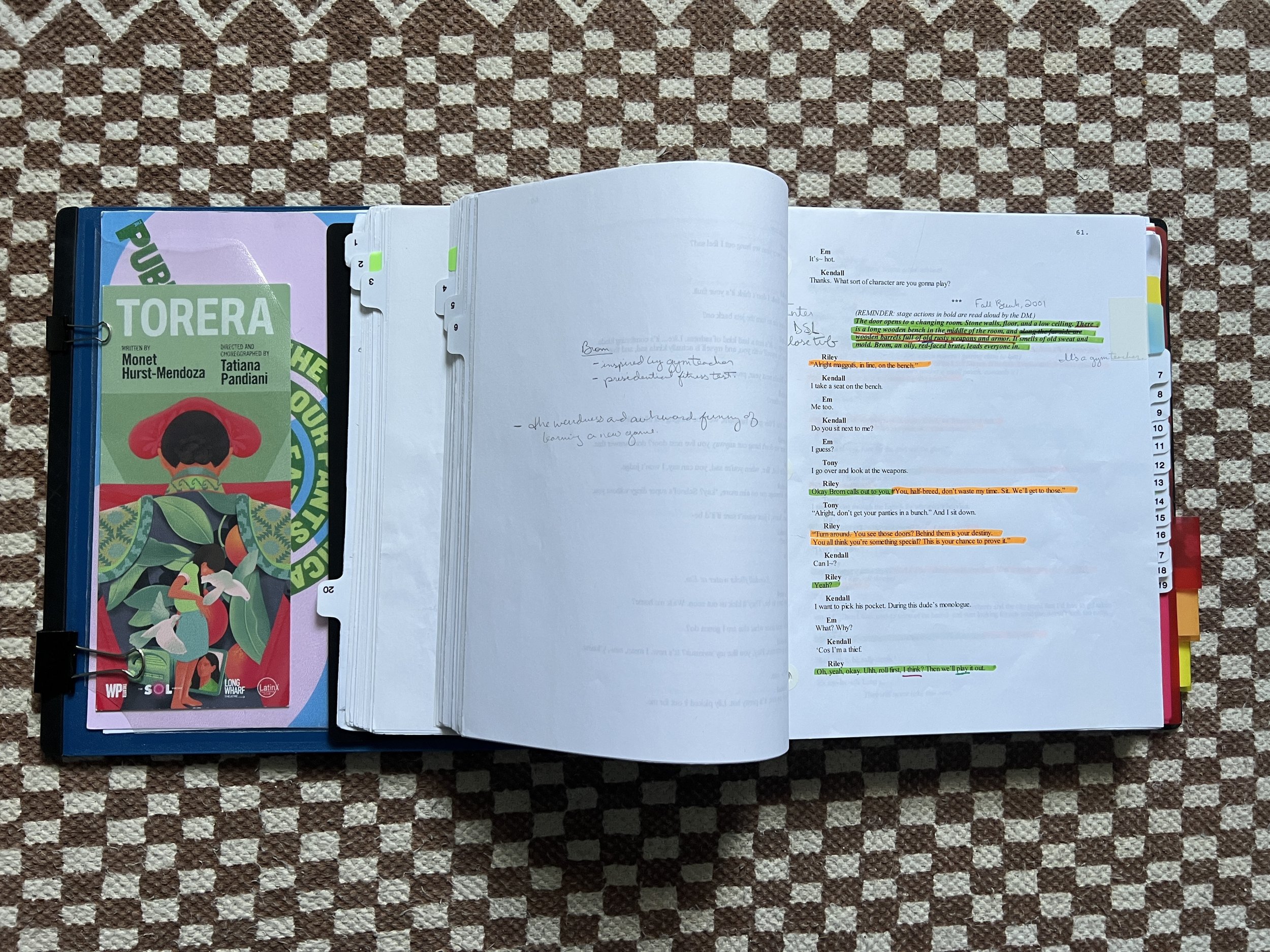

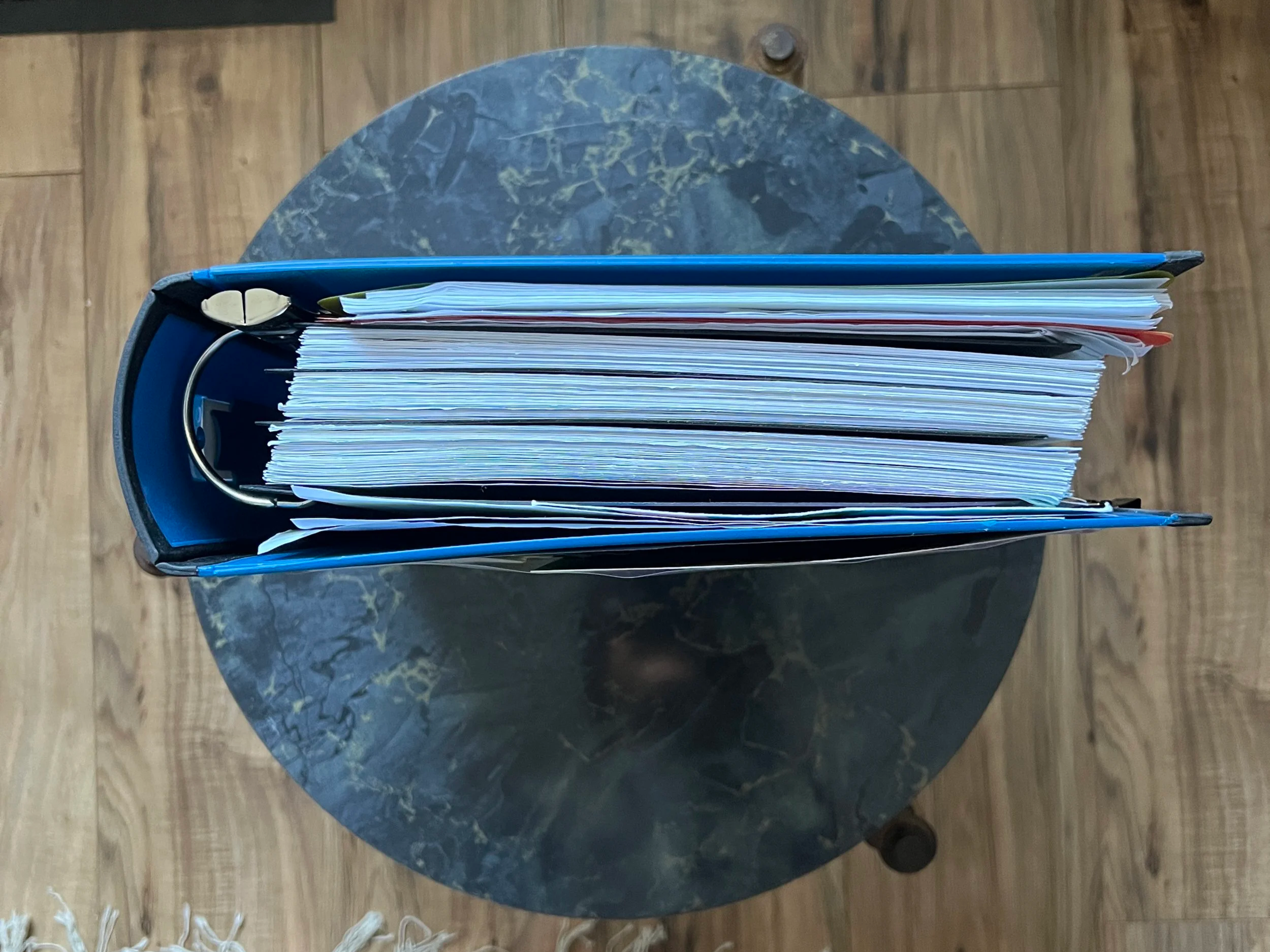

So once The Mousetrap opened at Berkshire Theatre Group, I started at the beginning of August at page one. I really got organized with everything. I’ll show you, because I feel like this was my Bible. [Holds up the Initiative script.] Everything is color-coded. Important actions and anything that Riley speaks is green. The AIM [AOL Instant Messenger] chats are all pink. The necromancer and any D&D is in orange. For every scene that I was in, I had an important quote from that scene that I could think of when I was going on stage. “Normal is death” was one of them.

“For two months, all I did was memorize lines,” said Greg Cuellar, whose chunky, color-coded script for the five-hour play Initiative is seen here. Photos: Greg Cuellar.

Initially, I prioritized memorizing anything that was huge chunks of text where it was just me speaking: a lot of the D&D stuff, Riley’s essay. Somewhere in my career I found the best thing for me to do is walk. I hike quite a bit in Los Angeles, so I would hike for five miles and bring a couple pages with me and just go over them, over them, over them, over them.

There has always been in the back of my little anxious brain, how am I going to do this? Once we were up and running it got better towards the end. But it truly was just one page at a time.

During the intermissions, I walked around the lobby in that slightly dazed state that happens after watching theater, but then it was quick, get back to our seats. Your Saturday evening shows had a 90-minute dinner break take the place of an intermission. Was that break easier or harder?

I hated it at first. Because it cools down my voice, my energy drops, I eat a meal, and then all of a sudden I’m kind of sleepy again. But I ended up really appreciating it because the Friday show would get out at midnight and I’d get home around 1 a.m., and then I would eat a rice cake and steam my voice and put on my heating pad. And then I was energized until like 2:30 or 3:00 a.m.

Then we had an early call for the matinee on the weekend. I had to do full-body makeup to cover up my tattoos. We got it down to roughly 45 minutes to an hour to cover six tattoos, twice a week. I wish I could go back to my younger self and be like, “Stop, stop, one day you’re gonna do a show at the Public and that hour every day, you’re gonna miss it.”

I would come in on Saturdays, do my touch-up, and by the time we got to that 90-minute intermission, I was grateful that I could actually go sit down. I could have another cup of coffee, I could eat food, and I always took a 20-minute nap.

You just set a timer and had faith that you would wake up refreshed?

Set a timer, put on my white noise, and sleep in that Equity cot. And I was not as social as the rest of the cast. I just couldn’t be. A lot of these folks in the cast have been best friends for a very, very long time with Emma and Else, and they’re part of a really tight-knit group of friends here, and I’m part of that group too, but I was just really focused on making sure that I was taking care of my body well enough that I’m not getting sick, I’m not hurting my back, and I’m energized enough to continue through all of this.

One cold and then everything implodes. So you were masked up and not touching the subway poles?

I wore a mask all the time. I washed my hands to the point of them cracking. I’d have magnesium and fish oil and branched-chain amino acids. It was athletic. It was an Olympic race.

You took a research trip to Cambria, the town which served as the inspiration for the “Coastal Podunk” setting. What did you discover there?

A lot of people assume that California is like Malibu or Los Angeles. And I knew that I wanted to go to have the visceral experience of what the town felt like.

My first reaction was, Are you fucking kidding me? This is where [Else and Emma Rosa Went] grew up. What privileged life allows you to be born in such a beautiful part of the world? And by the end of day three, I was like, there is nothing to do here. There is absolutely nothing but to go to the beach and stare at the water.

It got into me. Texturally, the pebbles of Moonstone Beach are so specific. It’s pebbles, it’s not sand. The way that the sun hits, that feeling of anomie that happens at sunset, where you really feel this experience of being on the edge of the world. And then to walk around the town — I think the median age of this town is like 65 — there’s no young people. It is a retired town. It is a town of newlyweds and old folks and tourism. Of course these kids are going to create a world much larger than the world that they are experiencing.

Snapshots of a trip to Cambria: Spanish moss, pebbles at Moonstone Beach, and the shoreline. Photos: Greg Cuellar.

The first night I went out onto the Moonstone Beach boardwalk by myself at like 11:30 p.m. I wanted to see what it would be like. And it was terrifying. You cannot see anything. And you can feel and hear the waves of the ocean hitting you. And I sat there and I did one of the monologues and just experienced that kind of isolation.

The second night I walked the entire length of the town, which is like a mile and a half one way, and I did the final monologue. They told me exactly where the bridge is that they based it on in the play, and I went there to capture in a very visceral way what those moments would feel like.

And it colored my experience in a completely different way to go to this cemetery that Riley will be, that Riley was buried at, this Catholic cemetery that’s up on a hill. It’s completely dirt and some of the graves are wooden graves from the early settlers of this area and the whole surroundings are covered with Spanish moss. And in this graveyard there were multiple graves of 16- and 17-year-olds who had died. One of them had died in a car crash, his grave was covered in beautiful decorations and things from his life, and it was clearly a place that his family was coming to a lot.

It stuck with me to see this is a kid who died in this town who did not reach his potential, and did not experience anything outside of what this world is, and how isolating it would be to grow up in a place like that.

Visiting felt like living in the play. I grew up in St. Louis and know the apartment complex that The Glass Menagerie is based on. And there’s that similar feeling of taking this pilgrimage to this town and the world you’re about to inhabit.

Bringing that world to the middle of Manhattan is such a juxtaposition. How did the production capture that feeling?

One of the cool things that helped was the expansiveness of the LuEsther. During rehearsals we were working in the Public Studios across the street and the ceilings are relatively lower. But once we got into the LuEsther, you could really feel that ocean experience of standing on the edge of the universe, on the edge of the abyss. A lot of that was incorporated with the incredible lights and the projections.

There were the waves that sort of crept up on the stage.

It’s the dream. Everyone was working at the top of their game.

Greg Cuellar and Carson Higgins as Riley and Lo in Initiative. Photo: Joan Marcus.

What’s the next mountain for you to climb?

In regard to this piece, I don’t feel like it’s the end. There has been such incredible feedback from critics, from audiences, from the administration at the Public that it feels like things are still bubbling. I think that there is room for this in the future.

In the beginning, it kind of felt like this swan song to my youth, and the things that my body is capable of doing right now in my mid-thirties. I will not always be able to act at this level and to sustain it for this long, and so it was this beautiful feeling of living at the absolute peak of what I’m capable of doing. But it is not sustainable living on any peak. I’ve sacrificed and lived a hermetic lifestyle. And so I’m partially excited to get back to being a human a little bit, to having some freedom to allow for other creative things to pop up.

Working on three shows this year was so fulfilling. So many artists, myself included, wait and wait and wait for that time where you feel like you’re recognized for the skill that you have dedicated your life to, and to come off of a year of full employment as an actor in the American theater, it was absolute heaven. I hope I can do it again.

My mentor Susan was a journeyman actor. She was in small parts in everything from Laverne & Shirley to Speed 2: Cruise Control. She had this vibrant career and life doing what she loved, and never fully got some insane recognition and was by no means a star. But I think that’s where part of my work ethic comes from. I just want to work. I just want to continue creating interesting characters, to keep doing work that allows introspection for myself, and can pay the bills every once in a while.

If I can set everything else up around me so that I can truly resonate with the experience of this character, then what else is there? What more could you possibly hope for?

This interview has been edited and condensed.