The Show Must Go On . . . at 5. Or 7. Or Midnight

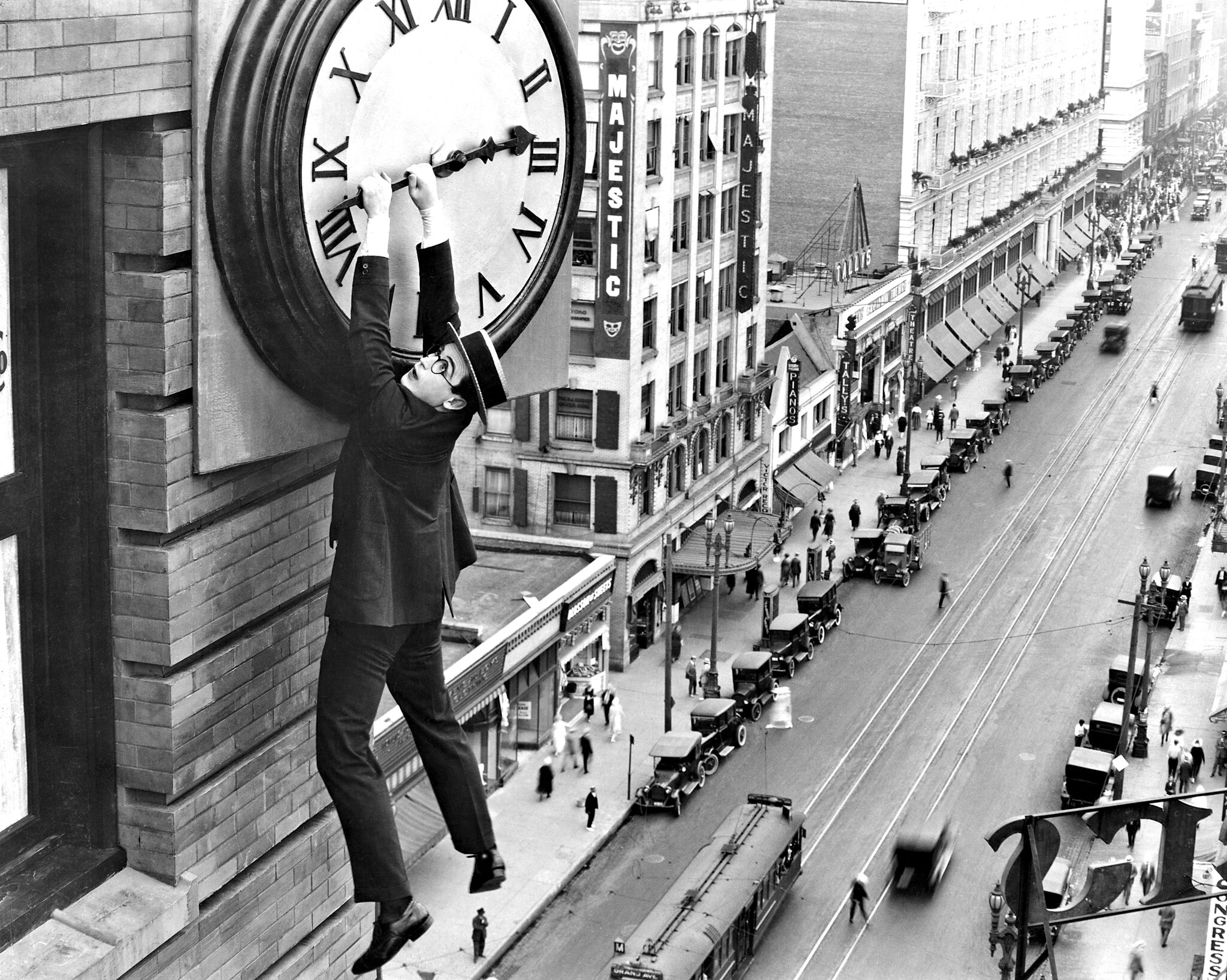

Theater companies, producers, and artists are upending traditional 2 p.m. and 8 p.m. curtain times. Photo: Harold Lloyd in Safety Last! (1923).

Dammit, Janet, Sam Pinkleton has a dream — to change theater’s traditional clock.

The Tony Award–winning Oh, Mary! director is overseeing the 50th anniversary Roundabout Theatre Company production of The Rocky Horror Show on Broadway this spring, and tells The Hat that he would love to schedule at least one performance of Richard O’Brien’s cult musical — and maybe more, if it can be arranged and agreed upon — with a start time of midnight.

The midnight showtime would match the famed late-night cinema screenings of the 1975 movie, and would be taking place — extremely fittingly — at Studio 54, the theater that was once the legendary nightclub. (On stage, there was a midnight performance of Rocky Horror when it was revived on Broadway in 2001 in aid of the Actors Fund.)

“If I could snap my fingers, if there was a way to do it that doesn’t kill the people having to perform and stage it, we would do midnight shows of Rocky Horror — no question,” Pinkleton said. “I understand why we can’t, because a lot of people would have to come to work to do it at that time. But spiritually, I would do one midnight show a week, and five other shows at 9:30 p.m. and no matinees.”

A spokesperson for Roundabout did not directly address questions from The Hat around whether midnight performances were planned, or if discussions were taking place about them. The times listed on the show’s website were the only ones currently finalized, the spokesperson said, adding that “things may be subject to change as we get closer.”

Even if Rocky Horror doesn’t start at midnight, some performances will end pretty near it. So far, Pinkleton said, there are Rocky Horror shows scheduled for 9 p.m. “and a couple of 10 p.m.’s, which is unheard of on Broadway. I’m very grateful Roundabout have been willing to have some imagination about the start times for the show. If I could, I would do mostly late-night shows for Rocky Horror. I don’t want to see Rocky Horror at 2 o’clock in the afternoon. It feels crazy to me.”

The Rocky Horror Picture Show’s midnight screenings led to its cult classic status. Photo: Mark James Miller, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

In its tweaking of traditional theater times, Rocky Horror is not alone (although by going late it is bravely bucking a trend for shows to begin earlier). Audience desires and tastes appear to be driving more experimentation from theaters and producers around scheduling.

“I’ve advocated quite fiercely for weird start times,” said Pinkleton. “I don’t know who made the rules about theater schedules, and — lovingly — I don’t care. It just feels one of many arbitrary things about the system, but not every show has to play by the same rules.”

“The greatest change to the consumer’s timeline was the pandemic”

“I have never regarded any theater as much more than a conclusion to a dinner, or the prelude to a supper,” the essayist and caricaturist Max Beerbohm once wrote. Today performance start times are now no longer restricted to the 2 p.m. and 8 p.m. curtains of yore. More and more productions, especially Off-Broadway, are trying out new start times to win over audiences who, in a city that once famously never slept, now seem to want to keep more regular hours.

“Today we have to tailor the start times of shows to when audiences want to go out, not when we want them to go out.”

For example, a heavyweight, star-studded three-hour drama that starts at 7 p.m. may be more palatable to audiences than one that begins at 8 p.m. In London last year, as reported in The New York Times, the National Theater introduced 6:30 p.m. start times.

Producer Ken Davenport recalls being surprised by “the sheer variety” of start times in the UK on a trip there in the early 2000s. In the US, theater-industry thinking around start times “is evolving very quickly,” Davenport said, as consumers have more options for entertainment and socializing. “Today we have to tailor the start times of shows to when audiences want to go out, not when we want them to go out.

“The greatest change to the consumer’s timeline was the pandemic: how they consumed entertainment, how they dined out, how they did everything, was thrown up in the air,” Davenport added.

A variety of start times is especially visible when it comes to shows of shorter (one and a half hour or less) duration. Liz Flemming, founder of Out of the Box Theatrics, which produced Douglas Lyons’s show Beau the Musical, explained that the show’s range of timings — including 1 and 5 p.m. starts —were decided when thinking about it as “a small, Off-Broadway show without a known IP, looking at who we were competing with, and when were we competing with them.”

If a ticket buyer, said Flemming, wanted to go out on a Friday night they could see Beau at 5 p.m. and another show at 7.30 p.m. “Part of the option of having unorthodox start times is being able to see our show, then Death Becomes Her afterwards,” said Flemming. An unusual start time helps people to notice a brand-new musical like Beau, she said. “It sets the show apart and marks it out as distinct.”

In planning Beau’s uncommon schedule, Flemming was inspired by the success of Titanique (heading to Broadway this spring), which featured 5 and 9 p.m. performances on Saturdays, at the Daryl Roth Theatre. The later slot didn’t work for Beau — although the show, at the Distillery at St. Luke’s Theatre, includes an actual bar as part of the set, intended as a nudge for pre-show libations — and Flemming initially didn’t think 5 p.m. on a Friday would either. “But for some reason, that’s the one that’s really selling for us. Maybe it’s because people feel it’s early enough to go to dinner afterwards. Or maybe it’s because Friday is a shorter working day for some people.”

Typically, 7, 7:30, and 8 p.m. are the most familiar evening performance start times, though post-pandemic, the 7 p.m. start seems increasingly popular with audiences keen for earlier ends to their evenings. While 7 p.m. performances aren’t new — in 2002 marketing firm Serino Coyne and publicists Boneau/Bryan-Brown trialed a “Tuesdays at 7” initiative — they are now far more prevalent.

“Having some specialness about performance times is a good thing”

Pinkleton is an evangelist for experimentation: Oh, Mary! led the way off and on Broadway with start times of 5 p.m. and 8:30 p.m. on Saturdays (more conventionally it plays at 2 and 6:30 p.m. on Sundays and 7:30 p.m. on weeknights). Pinkleton also directed Josh Sharp’s ta-da! and Morgan Bassichis’ Can I Be Frank?, which had a variety of start times: 5, 7, 8, and 9 p.m.

At the renovated Cherry Lane Theatre (now owned by movie studio A24), performances of Natalie Palamides’s Weer began at 9 p.m., while Clare Barron’s forthcoming play, You Got Older, starring Alia Shawkat, features an array of showtimes. (An A24/Cherry Lane spokesperson declined to comment on the shows’ scheduling.)

“What we’re doing with start times hasn’t been working,” Pinkleton said, adding that the right time is particular to each show, both in terms of content and the kind of audiences it wanted to attract. “The positive read of finding successful new times is, ‘If you build it, people will come,’” Pinkleton said. “I’m way more likely to go to a show if it’s a weird time that doesn’t conflict with anything else. Oh, Mary! has been confidence-giving to a lot of theater people.”

Director Sam Pinkleton is helming The Rocky Horror Show revival at Studio 54 in March 2026. Photo: Marc J. Franklin.

“Right now, I am making a lot of gay stuff for drunk people,” Pinkleton said, laughing. “I think some things are better experienced at nighttime. I was there on the night of the midnight performance of [Lucas Hnath’s] A Doll’s House, Part 2 in 2017. It was the most exciting night ever. Having some specialness about performance times is a good thing. It makes the show feel like an event.”

Pinkleton said 5 p.m. shows have allowed theater devotees to see three shows in a day — one at 2, one at 5, and one at 8 p.m. It also gives people social flexibility, as they’re able to make plans for drinks, dinner, or meet friends before or after.

What do actors prefer? Tony Macht, who has played Mary’s Husband’s Assistant and Kyle in Oh, Mary! on and off Broadway, loves the show’s 5 p.m. performances.

“All actors are somewhat nocturnal,” Macht told The Hat. “When you’re forced to do 2 p.m., even though it’s 2 p.m. it feels like you’re performing at brunchtime. It’s horrible, you’re barely awake. You do warm-ups obviously, but you can sometimes hear it in your voice and think ‘Oh shit I wasn’t ready for this one.’ 5 p.m. is great and universally loved by the Oh, Mary! cast. Also, the audience has had time for at least one drink by then, so that’s helpful.”

“All actors are somewhat nocturnal. When you’re forced to do 2 p.m, even though it’s 2 p.m. it feels like you’re performing at brunchtime.”

For Macht, a later start time “means I can get stuff done: laundry, brunch with friends.” Without a long gap between shows “you can use the energy from the first show to take you into the second, so it’s like one big double performance. It’s oddly invigorating and feels like doing a doubleheader in baseball. The gap between shows on a 2 and 8 p.m. day feels more like starting the whole engine up again, and more exhausting.”

Condensed showtimes might also provide more balance to performers and theater artists with families, partners, and children, or if they’re single, just in terms of opening up daytimes and evenings. Start times don’t just affect audiences — actors feel their impact keenly.

Matt Rodin, who plays lead character Ace Baker in Beau, said his favorite two-show combination was 1 and 5 p.m. on Saturdays.

“I can wake up at a decent time, have the morning to myself, feel energized to do the shows, then be home by 7:30–7:45 p.m., watch a movie, and have a regular evening with my husband,” Rodin told The Hat. “The body has time to calm down, reset, and be ready for the next day’s shows. I didn’t like the 9:30 p.m. performances when we were doing them. It meant a late finish. There was something about a later performance time that is more taxing on the body.”

Rodin said he also prefers a shorter window between performances on a two-show day, “although that’s just me. All actors are different. Some like to see their families between shows, or have meals. I’d rather stay in show mode and do it again, then get out of there. I’ve fallen in love with the 5 p.m. time slot. My husband has a 9-to-5 job, so being able to go home and spend quality time with him has been amazing.”

“I’ve been really surprised by the Fridays and Saturdays at 5 p.m. performances,” said Flemming of Beau’s schedule. “For whatever reason, they’re full. We sell them out, and people come. The 9:30 p.m. we noticed wasn’t a huge hit for people. We changed it to 1 p.m. and that seems to be going a whole lot better. To be honest, we’re hitting an older demographic, and they seem to enjoy having the option of going to an early time. I think the appeal for them, and me personally, is the idea you’re getting home earlier if the show starts at 7 p.m.”

Matt Rodin in Beau the Musical, which experimented with unconventional curtain times during its Off-Broadway run. Photo: Valerie Terranova.

“Shortened attention spans are not new, but since the pandemic we’re not competing with other theaters — we’re competing with streamers, concerts, and movies,” said Rodin. “Starting a show at 7 p.m. makes it more accessible to people who may want to go home afterwards to watch a movie or do something else.”

Another difference with Beau: the show’s day off is Tuesday, rather than the industry usual of Monday, meaning, said Flemming, that Monday shows tended to be heavily populated by “theater industry people on their day off.”

“When there’s a really hot show with a really weird start time, you’ll go”

There seems to be room to maneuver when it comes to performance times, within regulated reason. A spokesperson for the Broadway League, the powerful trade association that represents Broadway theaters and producers, told The Hat that the League could not provide a representative to speak on the matter. “Each show makes their schedule independently and we are not involved in any industrywide decision making,” a spokesperson said in an email.

Karyn Meek, Senior Business Representative at Actors’ Equity, said that performance-time schedules were set by employers, following the provisions of the particular contract they are using (and there were “many different” contracts nationwide). Generally, Meek said, theaters and producers cannot mount shows too early in the morning, and there has to be enough time — at least an hour and a half — between shows on two-show days for performers to have a dinner break.

Meek said employers tend to set production times according to when they think audiences will most likely attend. “Post-pandemic, public tastes have changed, and that may change production times,” Meek said. “As the saying goes, ‘You go where the fish are.’”

Finding those fish is a challenge. In addition to changing audience time-tastes, there is a forecasted decline in the number of tourists coming to New York due to negative feelings toward the Trump administration.

Alongside industry stipulations, the clock itself is an integral part of theater-making’s practice and versatility. Oh, Mary! producer Carlee Briglia, who with Mike Lavoie runs Mike & Carlee Productions, said their showtime experimentation began with Rachel Bloom’s Death Let Me Do My Show, at the Lucille Lortel Theatre in 2023, which ran on different days at 5:30, 7, and 8:30 p.m.

“We were inspired by American Utopia’s matinees [which ran at 2 and 3 p.m., and one at 5 p.m. on Broadway], which my parents were thrilled to travel in from New Jersey for,” Briglia said. She and Lavoie subsequently offered unconventional start times for other shows they produced, including Alex Edelman’s Just For Us, Kate Berlant’s Kate, Hannah Gadsby’s Woof, ta-da, and Can I Be Frank?.

“The theatre is an attack on mankind carried on by magic: to victimize an audience every night, to make them laugh and cry and suffer and miss their trains,” Iris Murdoch wrote in her 1978 novel, The Sea, The Sea. Since COVID, audiences might at least have a better chance of making their trains on time.

“When there’s a really hot show with a really weird start time, even if you’re not thrilled with the time, you’ll go — it all depends on people’s appetite for the show.”

“The pandemic changed people’s relationship to what a night out is, and their behavior when it comes to going out on those nights,” said Briglia. She pointed out that she had been able to experiment with Oh, Mary!’s start time because of its popularity. “If we know people want to see a show, we can get to be more adventurous with a show’s start time. When there’s a really hot show with a really weird start time, even if you’re not thrilled with the time, you’ll go — it all depends on people’s appetite for the show.”

Neil Pepe, artistic director of the Atlantic Theater Company, told The Hat there had been a “slight change” over the last couple of years toward 7 p.m. starts at the venue’s main theater. “It feels like since COVID that more people are liking to go out earlier and getting to bed earlier.”

Pepe recalled one recent Atlantic show that featured — because of actors’ availability — an 11 a.m. performance on a Sunday, which audience members enjoyed being able to schedule a post-show brunch around. Because weekday matinees are traditionally harder to sell Off-Broadway, the Atlantic sometimes jettisons them in favor of four-show weekends.

Pepe has lived in New York since 1985 and fondly remembers its vibrant nightlife of bars and restaurants, especially Florent in the Meatpacking District, where he and friends would go eat at 4 a.m. after the “rock and roll atmosphere” of late-night performances in downtown theaters.

“There used to be tons of restaurants open later than 10:30 and 11 p.m. Since the pandemic that hasn’t been the case,” Pepe said. “People have gotten used to not staying up late, staying inside, and getting up early. There are few places open to eat in New York after 11 p.m.”

“It’s the end time people are more focused on, rather than the start time”

How conventional matinees are viewed and attended has opened up thinking about the industry’s most traditional time slot.

“Regular afternoon matinees can be good, necessary, because for some people they are the only times people can go,” Pinkleton said. However, there is “not a ton of enthusiasm” for matinees for performers, he added. “Actors want responsive audiences — and the cliché is not always true, but matinees are typically quieter and less fun. Sometimes the late shows of Oh, Mary! are so loud they’re overwhelming and that’s not great. But no one’s racing to do more matinees.”

When Davenport was producing A Beautiful Noise: The Neil Diamond Musical on Broadway in 2022, he said he received a “tremendous amount of feedback” from his older-skewing audience that they wanted more matinees. “We made 50 percent of our shows matinees,” Davenport recalled, “including a Thursday afternoon matinee. That replaced our Wednesday evening performance, which for any show is the hardest show to sell.”

The move was very successful. “It made a two million dollar difference at our box office,” Davenport said. “A Thursday afternoon was also good because no other show did it, so we had no competition in that slot and it also set us apart. Sixty-five percent of our audience were tourists, and they told us they were glad we were doing it; it meant they could squeeze in one more show on their trips. Now that may not work for Oh, Mary!, but they’ve figured out doing something different and distinct that works for their hip, young, cool audience with their 5 and 8:30 p.m. shows.”

For Macht, the 2 p.m. Oh, Mary! matinee audience can feel more restrained than the boisterous later audiences. “We often say, ‘That was pretty good for a matinee,’ but I would also love a scientist to study whether we’re feeding into that familiar projection and stereotype around matinees being underwhelming,” Macht said.

Tony Macht, Cole Escola, Conrad Ricamora, and Bianca Leigh in Oh, Mary! on Broadway. Photo: Emilio Madrid.

“The Saturday 8:30 p.m. performance is best,” he added. The audience has had time for a drink or two, and most of them don’t have to work the next day, whereas Sunday at 2 p.m. is different. “You probably went out last night, you may be hungover, trying to sit in an uncomfortable chair. The audience can be a bit crankier, and it takes a bit longer to get them going. As performers we feel all those different crowds.”

Rodin noted that Beau’s 1 p.m. and later evening audiences are different (the early afternoon ones tend to be older, he said); he can tell by the volume and nature of the applause to the opening number what kind of audience it is, and where to pitch his performance accordingly.

With Oh, Mary!, Briglia started programming Thursday shows at 5 and 8:30 p.m. in the summer, after judging — at that moment — there were more tourists in the city, and people working from home had more flexibility to attend performances.

Dovetailing with the issue of when shows begin is how long they are — Davenport notes that the current general audience desire is for shorter shows. “It doesn’t mean they won’t sit for longer periods of time, but if you’re selling people tickets for shows that are 2 hours and 45 minutes, it needs to be that much better and have buzz. They will sit down for a long production — look at the success of Stereophonic. When something is that good they will come, and then tell all their friends to come see it.”

Pepe is heartened that there remains “a real hunger” for live performance; now theaters, particularly Off-Broadway, have to try to figure out “the balancing act” of attracting audiences while footing the bill for rising production costs, and “finding our way back slowly but surely from the pandemic. We’re figuring out how to make it work the best way we can.”

For Pepe, “there is no hard-and-fast rule” over the actual lengths of productions. Audiences, he says, will come to short and long shows, according to the quality of the work and the buzz around whether people really want to see it.”

As with most things, there is more flexibility — and adventurousness — around start times Off-Broadway, said Davenport. Experimentation is especially important Off-Broadway, Briglia reasoned, “because it’s hard to find eight showtimes in a week Off-Broadway, a lot of comedy shows are doing seven,” noting that a traditional Saturday matinee is an odd time to do a comedy.

Should there be more experimentation with performance times? “A thousand percent yes,” said Pinkleton. “I am a fierce advocate for seeing what a show needs. That might be a traditional performance schedule, but it also might not. Later this year I am also hoping to do something quite family friendly, and for that I’m hoping we can do 11 a.m. shows.”

In terms of other distinctive start times, Flemming would — like Pinkleton — “love to explore the market for late-night shows, after 11 o’clock. I don’t think the actors or myself might like it, but I’d be curious to see how it would go — if we market it with a bar and live band before, then the show after.” Flemming would also like to see what show could best work Off-Broadway with a conventional 2 p.m. matinee time, or even a morning show “like the morning movie,” that could attract a different crowd.

“I think people crave the stability of a regular Broadway schedule, but I also think we can deviate from it — depending on the show — to give audiences fresh options,” said Briglia.

While some actors may welcome the experimentation, Macht said behind-the-scenes technical and other workers may feel differently. “They are often there before we get there and after we leave,” he said. (A spokesperson for the union IATSE did not return requests for comment by deadline.)

A truly late-night show — an 11 p.m. start, for example — might only be attractive to audiences when New York nightlife itself reawakens, Briglia said. “Producers and theaters are always trying to figure out who the core audience is for a show, and what appeals to them. Time of year matters. In the summer we find weekdays sell faster than weekends, but in spring, fall, and winter, Friday and Saturday night shows are usually the best shows of the week.”

Pepe invoked other positive models of invention: theater festivals that feature multiple shows a day, and conventional afternoon matinees at upstate theaters “that sell like gangbusters, because that’s when upstate audiences like to go to the theater.” He also points to productions like Heather Christian’s 2024 show Terce: A Practical Breviary — “a radical rethinking of a monastic 9 a.m. mass” — at the Space at Irondale in Brooklyn, which began at 9 a.m.

Davenport — who’s currently developing Slumdog Millionaire as a stage musical — wonders if trying out 5 p.m. curtains on Fridays might be fruitful, as well as 11 a.m. shows for productions geared at families and children. While Davenport thinks the 7 or 7:30 p.m. curtain time is ascendant, he also has heard from tourists who prefer the 8 p.m. curtain because they feel a little rushed by the 7 p.m., “as it’s cutting their tourism day by an hour.”

Also, Davenport ponders, if showtimes themselves are getting shorter, “could we return to 8 p.m. if it means that audiences can expect to be out at 9:30 p.m.? I would argue it’s the end time people are more focused on, rather than the start time.”

However, recent research, Davenport added, showed a falling suburban audience from the New York metro area. “They want to get home. They may even say, ‘Keep it at 7 p.m. We don’t care if it’s a 90-minute show. If we’re out at 8:30 p.m., we can be home by 9 p.m.’ People want to be in their pajamas now.”

“Giving people more options is better for everybody”

Macht “can’t wait” to see what hours Rocky Horror ultimately keeps, and would “love” to perform in a late-night show himself, as long as it abided by all union rules and had the agreement of those working on it.

“It’s a risk doing a show in the middle of the night,” Macht said. “If it’s boring, people might fall asleep, but if it’s exciting it can be electric.”

Rodin also hopes Rocky Horror experiments with radical start times — and theater more generally learns from its example. “Do they try to do later night shows, and what does that do to an audience? It will be fascinating to see. Theater is about pushing boundaries — and figuring out what works and what doesn’t.”

“Giving people more options is better for everybody,” Davenport concluded. “My dream for anyone in New York who wants to see a show is that it shouldn’t matter what time of day it is — there should be a show for them to see.”