David Cale on the Art — and Challenge — of the Solo Show

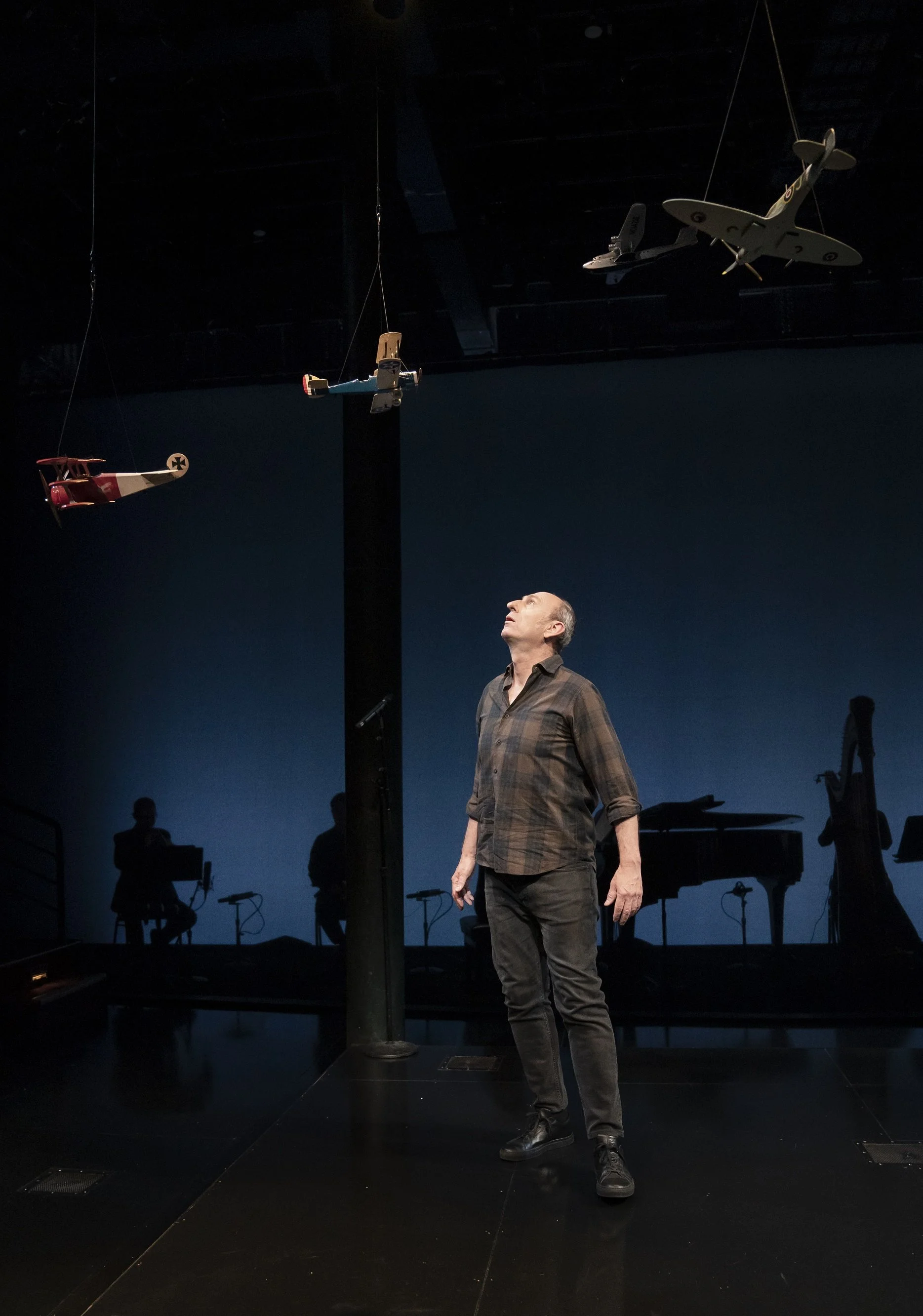

David Cale in rehearsal for The Unknown, his new solo play starring Sean Hayes and directed by Leigh Silverman at Studio Seaview. Photo: Austin Ruffer.

British-born David Cale began writing and performing solo shows in 1986 with The Redthroats, the story of an imaginative and awkward British boy whose childhood is spent dreaming of stardom à la Judy Garland and life in America. His many pieces include Lillian, Palomino, Deep in a Dream of You, and, most recently, Blue Cowboy, about the romance between an East Coast writer and an Idaho cowboy, seen at Bushwick Starr in fall 2025.

His autobiographical solo musical We’re Only Alive for a Short Amount of Time, revealing his own traumatic childhood and family tragedy as well as his emigration to the US, was seen at the Public Theater in 2018. His solo works performed by other artists are the noirish mysteries Harry Clarke and Sandra, featuring Billy Crudup and Marjan Neshat, respectively, both of which premiered at the Vineyard Theatre.

Cale’s latest, The Unknown, a thriller about a writer featuring Sean Hayes, debuts in February at Studio Seaview. Cale spoke during rehearsals about the development of his solo work and why he remains wedded to the form.

HOWARD SHERMAN: Solo show, one-person show, monologue, one-man play, monodrama, monologist — there are all of these terms relating to pieces done by a single performer alone on a stage. Do you think that they carry different meanings?

DAVID CALE: When I started, because I never worked with a director for the first eight years, people kept calling me a performance artist. And I always thought that “artist” was a gift word. You didn’t give it to yourself. Other people gave it to you if they thought you were such a thing. But I always wanted to straddle the performance world and the theater world.

When my first show The Redthroats started at PS 122, and then reopened at Second Stage, it was still without a director. But as a consequence, a number of theaters across the country, as well as performance spaces, wanted to present my work. But the theaters said, “Please, if you do an interview, don’t call yourself a performance artist, or nobody will come.” That it will put their audience off. Because I felt that I shouldn’t call myself an artist at that moment, I never quite knew how to describe what I did. I sort of landed on monologist.

Billy Crudup in David Cale’s Harry Clarke at the Vineyard Theatre in November 2017. Photo: Carol Rosegg.

I think it does affect people to some degree, what you call it. But of late, because I’m doing this [The Unknown] with Sean and having done the shows with Marjan Neshat and Billy Crudup, they have been called plays, which is fine, but I don’t really think of them that way. I guess they are solo plays. I just sort of intuitively write them.

When you began, was creating solo pieces your original goal, or was that a practical decision simply designed to help you get work up?

I started off initially as a singer, and then as a songwriter. How it all began was I was singing in clubs around the city, open-mic singing other people’s songs. And it wasn’t working. I set myself a deadline: Folk City, which was on 3rd Street, had an open mic on a Monday, and I thought, I’m going to buy myself a guitar — I’d never played and didn’t know how — and in a month, I’m going to do two or three original songs.

A friend of mine thought the lyrics were better than the melody, and said, take them to St. Mark’s Poetry Project and read them. I was so frustrated because I’d been doing all these open mics with other people’s songs, so I sort of hurled these spoken songs out. It got a much bigger response. They were like mini-monologues.

Then somebody there said, take them to the Westbeth Theater, which was doing a Monday evening of performance exploration. I started doing stuff at Westbeth, basically spoken songs and these sort of poems. And then they became more and more theatrical. I assembled an evening of them — which I did at Franklin Furnace, which was then in Tribeca — and Mark Russell moved it into PS 122 and there was no director.

I was just trying to express myself, and the form was kind of finding itself. I was never trained as an actor. I was never trained as a writer. In The Unknown, at one point the writer in it is like, “How do I ever start writing? I know, where did this begin?” I didn’t want to be a writer, but I was very dogged in terms of working, and one thing evolved into another. I was finding my own voice, where I never really had a voice.

It wasn’t intentional. It kind of caught a wave in the mid-80s to late 80s, where there was a lot of interest in solo shows. I was very unselfconscious about things. I think there was a purity to what I was doing, without saying how good it was or not good. There was the intention. It wasn’t geared to a career. I was trying to express myself. And I think it just suddenly caught on.

I’d been working in a mail room, and then suddenly I’m at the Goodman Theater and running a show and running a show at the Taper in LA, and it kind of bolted out. I was getting a lot of press attention without making any effort. I was overwhelmed by all this. I was sort of hiding. Literally. I mean, Richard Avedon saw me twice, and I was too timid to even come out into the lobby. I was not show bizzy in any way. I went the other way. I was so shy of it all, but on stage, I wasn’t shy. If you lit me, if I couldn’t see the audience, but I could just focus on what I was doing, I was fine.

If you were shy, what drove you to want to perform?

I could control it. It wasn’t the driving force — to control everything — but I think I’d found a way to create a world where I was calling the shots. Because there was no director, there was initially no set designer, there was no costume designer, no sound designer. I did it. I did everything and it worked.

It was very instinctive. And it still is. It still is. I mean, when we talk about The Unknown, I can’t remember even writing. It’s been written very recently, but it’s still like, “Where did this come from?”

Psychologically, my life as a child and a young person was so dramatic and chaotic and I had no control. I was pulled around in the currents of the events of my childhood. And I think, without being conscious of it, I could create a world on stage. Aside from the fact I was expressing myself, I could also control it. And I’d never had that as a kid.

Since you started writing lyrics that became spoken-word pieces, was there a major transition for you, shifting from writing lyrics into something more colloquial?

Well, I realized I could sort of act, and so I started to play different people within these monologues. I started adding characters. I read in a publication — I don’t know how accurate it was — but Linda Ronstadt was quoted as saying, “I finally learned how to sing. It’s too bad I had to do all my learning in public.” I felt like I was learning in public, because there was nobody guiding me, and I would pick up little bits and pieces, I would get nuggets of things that helped me. Then it just got more and more theatrical.

Do you write or do you get up and improv and record yourself?

I never record. No, I write out loud. It’s very important that it’s out loud, because it’s not literature. It needs less words. It’s like lyric writing: you’ve got to leave room for the performance; whereas literature would fill in the description of how it’s said, or something.

Certainly with The Unknown, it’s constantly paring the text down with Sean’s performance. You don’t just say it. You can get it from what he’s doing. You know, it was the same with Marjan and Billy. If you get these really, really superb actors in there, you just don’t need some of the text.

Marjan Neshat in David Cale’s solo play Sandra, directed by Leigh Silverman, at Vineyard Theatre in November 2022. Photo: Carol Rosegg.

I don’t write into a computer. Everything is written longhand. And it’s out loud. If I don’t do it out loud, I have to go back and redo it, like read it back out loud, and it just sounds too heavy. If it’s not written out loud, it doesn’t have wings, so to speak. It’s like a thud. It has to be light on its feet. Then I type it into the computer, then I print it up, and then I rewrite constantly, and the revisions are written in pen and then I’ll type in the changes and print it up again.

When you write out loud, are you in character?

This morning, I ran The Unknown myself, because there’s a piece that’s not there yet. It’s missing. It’s not like it’s something that needs to be reworked. There’s a missing paragraph, and it’s driving me crazy. So I thought this morning, I’m going to run it myself. And then I thought I’ll come into the theater and run it. And then I said, “No, you won’t. You’re not coming in here, and Sean walks into you running the show.”

But that’s how I’ve been doing it. I ran Sandra, I ran Harry Clarke. I tried Harry Clarke out in Pittsburgh myself, just to see if it would work. Sandra I read in Pangea, a club in the Village, because I wanted to see if it would potentially work. I can tell when they’re in front of people, I can just tell when things are right when they’re interacting with people.

How does a director function for you? Do they become a dramaturg?

Leigh Silverman’s such a brilliant dramaturg, and that’s from somebody who controls like crazy. If Leigh tells me to cut, I’m so malleable. “Do you think you need that line? I don’t think you need it.” “Okay, let’s move it.” So she has a lot of input in editing the scripts, and occasionally suggesting a direction that the script hasn’t gone in, which I will then write. But it’s very unusual for me to do that.

I’ve had shows ruined by directors. I would say ruined, [though] the show’s done well, but I’ve hated the production. That’s very complicated. I’m performing in it, and I can’t change anything once it’s set. I can’t change the script. It’s hell for me to be trapped in my own show, and it’s been well received, and it just feels dishonest.

Sean Hayes, Cale, and director Leigh Silverman in rehearsal for The Unknown. Photo: Austin Ruffer.

I would love to have a hit, but it has to be on my terms. It has to be something that is approached with complete integrity that happens to become a hit. I can’t try and fashion something hoping it will be popular and increase my status or benefit me in superficial ways. I don’t want to lose integrity.

I think you need to get really overqualified people on my shows. I need people that have nothing to prove. In the past, I’ve had somebody that was trying to make their career. Sometimes you don’t need to do anything with me, and so to try and do something is just too much. It’s a tricky thing. I don’t think I’m the easiest…

. . . when you’re both the writer and the actor.

Yeah, that’s the thing. I’m very directable in terms of plays. I did one play where I was doing exactly what the director told me, and I got clobbered in the press for it, really kicked around, and it was kind of fascinating, in a way, but I was doing exactly what I was told. I’m not a resister.

How did you decide with Harry Clarke that you weren’t going to perform it?

It was decided for me. Sarah Stern of the Vineyard sent it to Audible, who were looking to venture into theater production. And Audible really liked Harry Clarke, but they didn’t want me to do it. They wanted somebody better known. And I had my show We’re Only Alive for a Short Amount of Time scheduled. I thought, if I do Harry Clarke, people will think it’s autobiographical. And I’m doing a very autobiographical show, and it’s really muddying the waters.

I’d never had an actor perform my shows before, and the fear was that people would say, “Oh, you could do it better,” or I would think I could do it better. So it had to be somebody really, really good. And I wanted Billy, and he was my first choice. He was Leigh’s first choice. Billy was not available. And I thought, I’m going to have to perform it, but I don’t think that was ever going to be an option with Audible. But then Billy became available. I kind of hit the jackpot, but I was afraid there would be a list of actors, and it would go further and further down, and it would get less and less exciting to me and more like, “Why am I being cast out of my own shows?”

You played Lillian, who was a middle-aged Englishwoman. Could you have played Sandra?

Yeah, I mean, but I couldn’t. I could do them all, but how good would they be? Sandra was written for a woman. I did perform Sandra because that’s how I try them out.

People said, if you’re not in it, you will be defined as a writer. If you’re in it, it’s another performance piece. Then what happened with Billy? That was the dreamiest experience with him in four productions of it. But all of a sudden, I’m the writer, and for years people said nobody can perform your shows for you, and I always thought that was wrong. People that I really trust, who are very knowledgeable, all felt the same thing, that the shows depend on me. I always felt they didn’t. Harry Clarke proved they didn’t.

Suddenly you’re the writer. Is there any desire to expand and write for multiple actors?

I don’t think my instincts are with multiple people. They’re either multiple people within a monologue or they’re film scripts. I just don’t have an ability or aptitude for plays. I’ve written a couple of short plays that I really like, but I don’t know. I am in awe of people that can write a two-hour play.

What is the power of one person embodying all the people in a story? Why are you drawn to that?

I really don’t know. What I was sensing with Blue Cowboy in Brooklyn was a different kind of thirst for one person telling a story that had authenticity. There’s something that was very human about one person getting up under some lights in front of a group of people telling a story that felt different to how it was, say, 30 years ago. There was something very human about it and honest. And a lot of people were waiting for me after that show, more than usual, telling me that they really loved sitting in a theater and hearing a story. And that’s basically what it is.

David Cale performing in We’re Only Alive for a Short Amount of Time at the Public Theater in June 2019. Photo: Joan Marcus.

They’re all stories. It’s not that I go and see a lot of solo shows or anything. I don’t feel like I was influenced by other solo performers, necessarily, beyond someone like Laurie Anderson — she influenced me early on — and I always loved Spalding Gray and Eric Bogosian. I love Karen Finley’s stuff, she really influenced me. And Holly Hughes. I don’t know what it’s about. I don’t know why I do them. I’ve got 14 solo shows. It’s like, what’s going on here? But I keep coming back to them.

Yet only some of them feel like autobiography?

They’re all emotionally autobiographical, I think. I feel like a singer-songwriter who, instead of albums, makes shows. That’s how I used to feel all the time. I still feel it to some degree. Deep in a Dream of You was 12 monologues, like 12 songs. Smooch Music was similar. They were like albums. They were laid out like Joni Mitchell albums, in my view.

There’s a lot of music influence in my work, and movies. I know movies much more than theater. So my shows have an eye on painting a picture that you want the audience to be able to visualize.

There’s two things going on at the same time: there’s the teller of the story, and then there’s the collaborator, which is the audience member, who’s seeing it, who’s making their own movie based on what they’re hearing.

This interview has been edited and condensed.