In “Jewish Plot,” Torrey Townsend Resists a Tidy Narrative

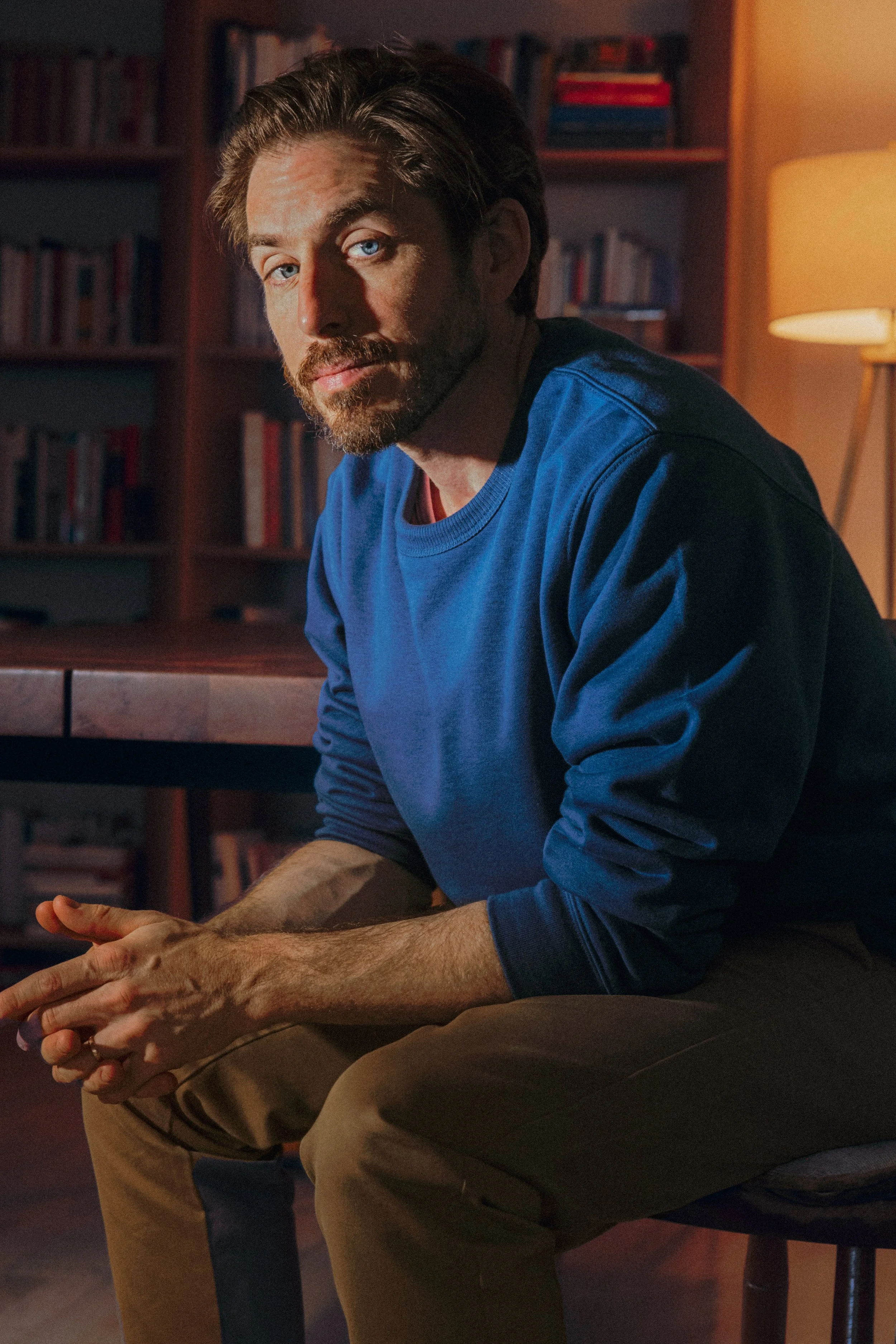

In his new play, Jewish Plot, Torrey Townsend uses a Victorian melodrama as a framework to explore authorship and identity. Photo: Matthew Dunivan.

Torrey Townsend has stopped trying to explain his new play to friends.

“I tell people it’s called Jewish Plot and I’d really like you to come see it,” he tells me. “Then I say, the less you know about it, the more you’ll enjoy it.”

For our purposes, I’ll give an overview: Jewish Plot, opening on October 28 at Theatre 154 and directed by Sarah Hughes, is a shape-shifting play about a writer (also named Torrey Townsend) who becomes obsessed with an 1889 melodrama that shocked Great Britain but has since been forgotten (also called Jewish Plot, written by Irwin Willoughby Bruntmole). No matter that the play, which tells the story of a Jewish nobleman whose love is stymied by the anti-Semitism of Victorian London, is entirely a product of Townsend’s imagination: it’s a framework for the wild deconstruction of authorship and identity that follows.

Instead of unpacking the plot, Townsend wants to talk about the project’s origin story. In 2022, while Townsend was visiting his parents in New Hampshire, Karoline Leavitt (now the White House press secretary) happened to be running for Congress in his parents’ district, and he attended several of her events. “She would talk about an international conspiracy,” he says, “about a cabal of globalists who want to destroy the West, in phantasmagoric terms, with echoes of classical anti-Semitic conspiracy theories.” To Townsend, that rhetoric was eerily familiar—like “an old record from the distant past” or “lines from Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta.” He considered writing a “straightforward” play about that ventriloquy of historical conspiracies. Then he looked closer to home.

As a writer, Townsend relishes the opportunity to skewer his surroundings. In 2017, after getting his playwriting MFA at Columbia, he depicted a playwright well past his prime and his self-absorbed students in The Workshop. After working at a theater company, he wrote an incendiary satire about the bias and hypocrisy of a large nonprofit theater company, Off Broadway, which had a buzzy Zoom production in 2021. If he was going to write about conspiratorial thinking and anti-Semitism, he was going to have to dig into his own life.

Townsend’s grandfather, Meyer Steinglass, started his career as a journalist covering the Brooklyn theater beat. He became a more political writer in the early 1930s, calling out fascists and the demagogues who aped their language, like the influential “radio priest” Father Charles Coughlin. When Townsend talks about Karoline Leavitt’s conspiratorial language, I hear echoes of his grandfather’s early writing about coded language furthering anti-Semitic tropes.

Townsend’s grandfather, Meyer Steinglass, in the 1930s. Photo: Courtesy of Torrey Townsend.

During the Holocaust, Steinglass helped found a charity providing aid to European Jews and funding refugee resettlement in Mandatory Palestine. By the end of World War II, he was one of America’s leading Zionist voices. In his later career, he helped raise 17 billion dollars for the state of Israel as the publicity director for the fundraising organization Israel Bonds. Some of this family history is represented in the play, as the fictional Townsend talks about his identity.

In real life, Townsend has warm memories of visiting his grandparents in the Bronx for Seders when he was a child. But after his grandfather died in 1997, Townsend says his connection to Jewish religious practice and the Yiddish culture of his grandfather’s youth was severed. While Townsend felt alienated from his Jewish identity, he says his grandfather’s Zionist ideology remained ever-present during his upbringing.

Townsend says writing Jewish Plot allowed him to reclaim part of his heritage. His grandfather’s legacy of speaking out about fascism, anti-Semitism, and conspiracy theories is important to him. But he also rejects the Zionist project that his grandfather helped build. “I’ve lost all opportunity to inhabit an authentic Jewish identity that celebrates Jewishness,” he says, “and I think that is something fundamental about Zionism: it’s an erasure of Jewish identity, not a celebration of Jewish identity.” Townsend says the trauma that shaped his grandfather’s generation led to a culture of silence about their roots.

Madeline Weinstein and Neil D'Astolfo in Jewish Plot. Photo: Ken Yotsukura.

Stepping back to the 1800s, Jewish Plot aims to understand what Jewish identity meant before Zionism—when Theodor Herzl, the father of modern Zionism, was still making a go of it as a playwright in Vienna. When the play’s historical framing device shatters and the story moves back to the present day, it reflects Townsend’s attempt to figure out if his identity can be separated from the Zionist project. “Jewish Plot wants to hold the unspeakable despair I have been feeling about this subject,” says Townsend. “How can one even use words when words are abused? And how can one claim an identity as a Jew when one’s identity as a Jew is used to justify genocide?”

Those questions, like so many parts of Jewish Plot, resist easy resolution. It seems fitting, then, that the production faced its own recent moment of chaos: just days before opening, an electrical fire at the Brick in Williamsburg, where the play was originally meant to be staged, forced the team to change venues and restart tech rehearsals from scratch. This made for a hectic week, but perhaps also a fitting metaphor. For a play that embraces rupture, contradiction, and instability as a means of getting closer to the truth, the act of rebuilding becomes part of the work. After all, as Jewish Plot suggests, identity isn’t something inherited intact—it’s something you assemble, interrogate, and sometimes even burn down to begin again.